Paul Tuns

The centerpiece of the Liberal government’s spending plans over the next five years is a $30 billion commitment to child care. It is a relatively small amount among the $614 billion in program spending in 2020/2021, which is schedule to fall to $475.5 billion in 2021/2022 before levelling off in the vicinity of $430 billion in the years afterwards. But unlike most of the new spending announced by Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland – $12 billion for continued pandemic-related “emergency” assistance, a further $17.6 billion boost for environmental subsidies, $5.7 billion for youth programs, $4 billion for technological upgrades for small businesses, $2 billion to kickstart domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity – the child care spending is designed from the outset to become permanent.

The centerpiece of the Liberal government’s spending plans over the next five years is a $30 billion commitment to child care. It is a relatively small amount among the $614 billion in program spending in 2020/2021, which is schedule to fall to $475.5 billion in 2021/2022 before levelling off in the vicinity of $430 billion in the years afterwards. But unlike most of the new spending announced by Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland – $12 billion for continued pandemic-related “emergency” assistance, a further $17.6 billion boost for environmental subsidies, $5.7 billion for youth programs, $4 billion for technological upgrades for small businesses, $2 billion to kickstart domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity – the child care spending is designed from the outset to become permanent.

Next year, Ottawa will spend $4.1 billion on daycare, up from $1.3 billion in 2020/21, before increasing about a billion dollars a year for the next four fiscal years, to $9.2 billion in 2025/26.

Delivering the budget, Freeland said, “Five years from now, parents across the country should have access to high quality early learning and child care, for an average of $10 a day. I make this promise to Canadians today, speaking as your Finance Minister and as a working mother: We will get it done.”

The devil, as they say, is in the details, and there weren’t a lot of details about how this money would be spent or how institutional child care will be delivered. By the end of 2022, before the full transfer to provinces is ramped up, Freeland promised that daycare spaces would be subsidized to cut the direct cost to parents in half, with the goal being a maximum fee of $10-a-day. Ottawa will need to work on agreements with each province about how this is to be achieved and what, if any, restrictions or regulations would be put in place as part of the bargain for taking federal dollars to pay for a provincial social program. The federal government would split the cost of daycare subsidies 50-50 with the provinces, and after the initial five-year commitment, Ottawa would be on the hook for $8.3 billion each year afterward.

David Macdonald, senior economist at the pro-universal daycare Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, said there was no clear plan on creating new spaces or increasing child care worker salaries. There is already a shortage of “early childhood educators” in the field. Still, Macdonald said, the program was likely “transformational.”

It likely will not be.

Aside from the government’s general inability to deliver on its promises, Ottawa needs 13 dance partners in the 10 provinces and three territories. Currently, only Quebec has a plan like that touted by the Trudeau government, and several large provinces seem cool to the idea of Ottawa interfering in a provincial jurisdiction. The day after the budget, Progressive Conservative governments in New Brunswick and Ontario, and the United Conservative Party government of Alberta, all poo-pooed the plan, saying that a universal daycare scheme fails to address the myriad ways in which parents arrange for their children to be looked after, and N.B. Premier Blaine Higgs criticized the Trudeau government saying the the daycare promise looked like a vote-buying scheme.

Liberals have been promising universal daycare for three decades, and the closest they’ve come to delivering it was when Paul Martin signed agreements with a number of provinces to subsidize daycare spaces in 2005, but those arrangements ended when Stephen Harper became prime minister. Justin Trudeau has talked about child care but it wasn’t until the pandemic that he seemed willing to put money behind his words. Freeland claimed that the pandemic showed that “without child care, parents — usually mothers — can’t work.” She added that “child care has long been a feminist issue; COVID has shown us that it is an urgent economic issue, too.”

Freeland said that universal daycare is social infrastructure, and the budget document states “It is the care work that is the backbone of our economy. Just as roads and transit support our economic growth, so too does child care.” But dig deep into the 739-page document and the government admits that their child care plan will have only the smallest effect on economic growth: 0.05 per cent or 1/20th of a percentage point.

Most media reports touted the child care spending as an “investment” in ending the so-called “she-cession” – the notion that the pandemic economy has disproportionately hurt women.

But there are critics that the media has generally ignored.

Andrea Mrozek, a senior fellow at the Cardus think tank, is not a fan of the Trudeau-Freeland daycare plan. She said in a press release, “The child care plan proposed in Budget 2021 is structurally opposed to equity for all families,” explaining: “All families will pay for the plan, but only families who choose or can access the type of care the federal government favours receive the subsidized benefit.”

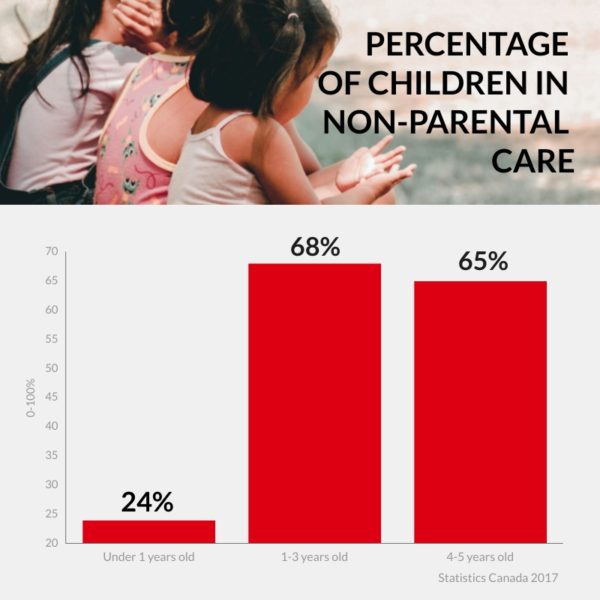

Mrozek has noted in previous Cardus reports that families choose different types of care based on their own situations, and many do not put their children in institutional care. According to Statistics Canada, about half of children under one are cared by for a parent, and only about half of all children under five who are cared for outside the home are in institutional, licensed daycare. Mrozek says that the Trudeau government’s policy does nothing to help the majority of families with preschool-aged children. She said, “supporting parents directly is the equitable way to help all families, regardless of the type of care arrangement they use, including caring for their own children,” explaining, “the proposed plan devalues the work parents and other caregivers do outside of an institutional setting.”

Mrozek said that “families know how to make the choices that work best for them” and “federal policy should maximize the flexibility of families to make varied choices across the country, emphasizing respect for these choices and decisions in the arena of caring for children.” On Twitter, Mrozek was even more critical of the government: “It took 50 years to get this because it’s a very bad idea.”

Helen Ward of Kids First said in a video release, “the government wants to coerce us, coerce parents and in particular coerce mothers into full-time paid work and putting our children into full-time daycare regardless of what we want. They think you are only working if you are in the GDP sector.”

That was the line taken by Conservative leader Erin O’Toole, who said during a post-budget scrum, “I’d prefer letting parents be in the driver’s seat and giving options to all Canadian families.” He has indicated he favours cash payments or tax credits given directly to parents that can be used for whatever each family deems most suitable for their situation. In 2006, the Conservatives beat the Liberals by promising $100 per month to every Canadian as an alternative to Paul Martin’s vision of subsidizing institutional daycare.