Korean fertility rate craters to 0.75

Paul Tuns:

Three recent news stories, a UN report, and a new study illustrate the challenge of precipitously declining fertility rates.

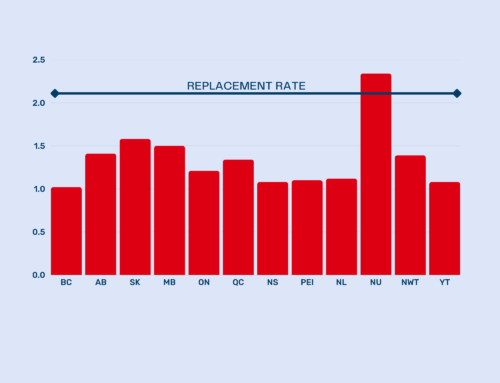

Demographers consider a fertility rate of 2.1 — the expected number of children a woman of childbearing age will have – as necessary to sustain a country’s population. Most western countries and large economies now have fertility rates well-below 2.1, with the United States having a relatively robust rate of 1.7, well under replacement.

South Korea has the lowest fertility in the world at 0.75, after a slight uptick over the last year from 0.73. In some urban centers it is under 0.5. Reuters recently reported that the South Korean military has shrunk 20 per cent as the cohort of 20-year-olds shrinks. Two decades ago, the miliary had 690,000 soldiers but today it has just 450,000. The population of 20-year-old men has fallen 30 per cent between 2019 and 2025, with just 230,000 of age to take the physical exam to enlist.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Red China is going to give an annual $500 USD payment for the first three years after a child is born to encourage families to have kids. China’s fertility rate hovers just above 1.0 after plunging from more than 1.8 in 2016. Red China instituted a one-child policy enforced by coercive abortion and infanticide in the 1970s amid fears of starvation caused by (communist policies). The policy was relaxed in 2015 and abolished two years later. Last year, 20,000 preschools catering to 3-5 year-olds closed.

The Financial Times reported that the population for England and Wales grew to new high of 61.8 million after rising by 706,900. Almost all that growth was through immigration as “natural population growth” – the number of births subtracting the number of deaths – was a mere 30,000. Official government statistics revealed a record number of 251,377 abortions in 2022 (the most recent year available) and the government estimates that one in three pregnancies end in abortion.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) report “The Real Fertility Crisis” denied that depopulation was a crisis but highlighted that “reproductive agency” is a “real crisis.” The pro-abortion UNFPA said that, in some countries, women, girls, and individuals who identify as LGBTQ are denied access to abortion or contraception but also admitted that many “face barriers to exercising the reproductive choice to have children.” Its survey in 14 countries found that 20 per cent of adults “believe they will be unable to have the number of children they desire” and that 39 per cent “reported that financial limitations had affected, or would affect, their ability to realize their desired family size.” Alongside calls for more abortion and contraception, the UNFPA called for “making parenthood accessible and affordable” through affordable daycare, paid leave for parents, secure jobs, and affordable housing.

Meanwhile, a study by Melissa Kearney of Notre Dame and Phillip B. Levein of Wellesley College found that “fertility has fallen to historically low levels in virtually all high-income countries.” The study, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, found that “short-term changes in income or prices cannot explain” the decline in fertility. They say “shifting priorities” reflecting a “a complex mix of changing norms, evolving economic opportunities and constraints, and broader social and cultural forces” are responsible for (mostly) women desiring and having fewer children. As educational, career, and personal opportunities expand, many women find what they may have to give up to have children – what economists call opportunity cost — to be more desirable than the prospect of having a child or more children.