Paul Tuns

On Nov. 24, Dan Quayle (not the former U.S. vice president) opted to be medically killed after he was unable to access timely chemotherapy for an aggressive form of esophageal cancer. On Oct. 7, he had been told that chemotherapy might prolong his life by a year. He was kept waiting for chemotherapy for ten weeks in Victoria General Hospital. The National Post reported that he “put on his best silly act for his two grandkids” to put on a brave face for his family even though he was in so much pain he was unable to eat or walk.

His stepdaughter, Shayleen Griffiths, said the family prayed Quayle would change his mind about being euthanized or that he would be able to receive the chemotherapy that might have made his life more tolerable. Her mother and Quayle’s partner, Kathleen Carmichael, had pressed the hospital to schedule chemotherapy but the doctors never provided a timeline, saying “we’re backlogged.” She told the Post “I think I could still have my Dan if he had gotten treatment sooner.”

Bioethics expert and lawyer Wesley Smith said that advocates claim euthanasia is about “choice” and “compassion” but that many patients, such as Quayle, do not feel that they have much choice when timely care is not an option.

In December, news broke of another patient, Samia Saikali, 67, who chose euthanasia after failing to receive timely care.

Saikala was having stomach pains in December 2022 and was finally diagnosed with stomach cancer in March 2023. She met with a surgeon in April who told her that she had stage 4 cancer and that it was inoperable. He said that she probably only had three to six months to live and that with palliative care and chemotherapy she might live for another year. Saikala was referred to the BC Cancer Agency where the case languished for ten weeks before seeing an oncologist, but it was too late for chemotherapy and immunotherapy because she developed other complications (perhaps as a result of waiting in the queue). After three attempts to receive chemotherapy, Saikala chose to be medically killed.

Saikala was having stomach pains in December 2022 and was finally diagnosed with stomach cancer in March 2023. She met with a surgeon in April who told her that she had stage 4 cancer and that it was inoperable. He said that she probably only had three to six months to live and that with palliative care and chemotherapy she might live for another year. Saikala was referred to the BC Cancer Agency where the case languished for ten weeks before seeing an oncologist, but it was too late for chemotherapy and immunotherapy because she developed other complications (perhaps as a result of waiting in the queue). After three attempts to receive chemotherapy, Saikala chose to be medically killed.

Her daughter, Danielle Baker, told Saikali she would publicize the “cruel” treatment from BC Cancer Agency that eliminated any chance of timely care to extend her mother’s life. “She said it’s too late for me,” Baker told the CBC, “but keep talking about it because everyone who’s coming after me (into the system) that needs to know and needs the help.”

The same week Quayle was medically murdered, Global News reported that another British Columbian, Allison Ducluzeau, opted to go south of the border for care when he was unable to access timely care in her home province.

Ducluzeau had just returned from Hawaii, where she had just married, in October 2022, when she started feeling abdominal pain. She was told it would take weeks to receive an appointment for an ultrasound and CT scan. She eventually went to the emergency department and a CT scan indicated she had peritoneal carcinomatosis, a form of abdominal cancer. Two follow-up biopsies revealed Ducluzeau had Stage 4 peritoneal carcinomatosis and she was referred to the BC Cancer Agency. Her family doctor said she would probably undergo high dose chemotherapy but the oncologist with BC Cancer suggested Ducluzeau was not a good candidate for chemotherapy as she likely had two months to two years to live and asked if she wanted medical assistance in dying – euthanasia – instead and encouraged her to get her affairs in order.

The newlywed refused to accept that diagnosis and looked for alternatives. She found one – in Baltimore, Maryland, at the Institute for Cancer Care at Mercy Medical Center. Attempting to contact her oncologist before heading south for care, BC Cancer Agency said it could be “weeks or months” to get another appointment.

Ducluzeau attempted to have her American medical bills paid by the B.C. Ministry of Health. Instead of compensation, she received a letter from BC Cancer Agency stating, “the services you chose to receive in the U.S. would not have been the recommended treatment for your cancer diagnosis.”

Alex Schadenberg, executive director of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition, said, “I guess euthanasia was the preferred treatment in B.C. because that is all Ducluzeau was actually offered.”

Ducluzeau told Global News, “I feel 100 per cent” and “There is nothing that I did before I got sick that I can’t do now.” She rides her bike, golfs 18 holes, and goes out for dinner with friends. “I started running again and I haven’t run for 10 years,” she said. She is back to work and spending time with her family. “I’m calling this my bonus round and I’m just trying to find joy in every day,” said Ducluzeau.

Schadenberg said most Canadians do not have the option to go to the U.S. for costly, out-of-pocket treatment. More problematically, the BC Cancer Agency that could not – or would not – provide timely cancer care was pushing euthanasia in lieu of timely care.

BC Cancer Care says that nearly 98 per cent of patients begin chemotherapy within 28 days once they have their consultation with an oncologist to determine treatment. The agency has not released the length of time it takes to meet with an oncologist or the length of time it takes to get the diagnostics completed before treatment is prescribed. Samia Saikala’s daughter Danielle Baker told the CBC “I really believe that our health care system and BC Cancer didn’t even put her in the ring.”

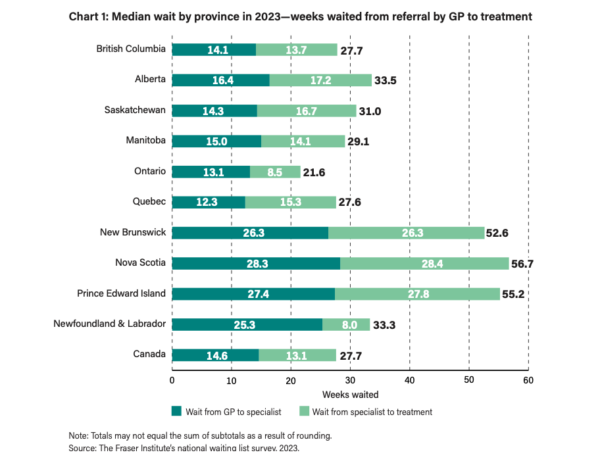

For three decades, the Fraser Institute, a Vancouver-based libertarian think tank, has been publishing an annual report on medical wait times in Canada. “Waiting Your Turn Wait Times for Health Care in Canada, 2023 Report” surveys specialist physicians across 12 specialties in all ten provinces to document queues for visits between a physician’s referral to a specialist and between meeting a specialist and receiving treatment (surgical procedures). Mackenzie Moir and Bacchus Barua, authors of the Fraser Institute report, found that the median wait time between a referral from a general practitioner to treatment was 27.7 weeks – “the longest wait time recorded in this survey’s history” and up nearly 200 per cent compared to the first report in 1993 when the median wait was 9.3 weeks.

The report states there is wide variation among provinces and specialties. Ontario has the shortest median wait at 21.6 weeks, while Nova Scotia has the longest at 56.7 weeks. British Columbia has the third shortest median wait times at 27.7 weeks.

Referrals to specialists are taking longer but the median wait between seeing a specialist and treatment fell slightly in 2023 from 14.8 weeks to 13.1 weeks. More importantly, the Fraser Institute reported that the wait times are still much longer than “what physicians consider to be clinically ‘reasonable’ (8.5 weeks).”

Furthermore, patients experience “significant waiting times for various diagnostic technologies,” including a median wait of 6.6 weeks for a CT scan, 12.9 weeks for a MRI scan, and 5.3 weeks for an ultrasound. Again, there were wide discrepancies among provinces.

The total number of procedures for which people are waiting in 2023 is 1,209,194, although some patients are in the queue for more than one procedure.

Moir and Barua say, “Research has repeatedly indicated that wait times for medically necessary treatment are not benign inconveniences. Wait times can, and do, have serious consequences such as increased pain, suffering, and mental anguish.” They can also “result in poorer medical outcomes—transforming potentially reversible illnesses or injuries into chronic, irreversible conditions, or even permanent disabilities.”

They also found that 1.8 per cent of patients leave the country to get more timely care; in B.C., that number is higher yet at 2.3 per cent.

In 2019, an Association for Canadian Studies survey found that health care, more than any of the 20 other items polled, was a source of pride in Canada. Nearly three quarters of respondents — 73 percent — said that Canada’s publicly funded universal health system was a very important source of pride in Canada – more so than the flag, passport, or any sports team.