Paul Tuns, Review

Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why it Matters, and What to do About It

by Richard V. Reeves (Brookings, $38, 242 pages)

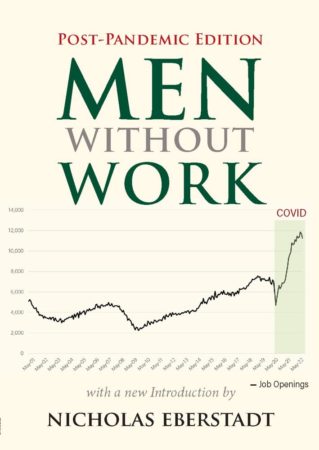

Men Without Work: Post-Pandemic Edition

by Nicholas Eberstadt (Templeton, $17, 238 pages)

Richard Reeves of the liberal Brookings Institute has written an important, if at times annoying, book about the plight of boys and men in today’s society. Of Boys and Men marshals an impressive numbers of statistics and studies to make the point that boys are struggling in school and men are not flourishing in their work or home lives, points that are too often ignored by those on the Left. Reeves makes the point that many on his side of the political aisle ignore the plight of boys and men because they erroneously think that it will detract from their work of promoting an equal society considering that women still lag behind men in some indicators (even as they now run at par or ahead on others). Reeves has the excellent line that liberals can be concerned about both equality for women and the struggles of boys and men because both are justice issues that cry out for attention.

Richard Reeves of the liberal Brookings Institute has written an important, if at times annoying, book about the plight of boys and men in today’s society. Of Boys and Men marshals an impressive numbers of statistics and studies to make the point that boys are struggling in school and men are not flourishing in their work or home lives, points that are too often ignored by those on the Left. Reeves makes the point that many on his side of the political aisle ignore the plight of boys and men because they erroneously think that it will detract from their work of promoting an equal society considering that women still lag behind men in some indicators (even as they now run at par or ahead on others). Reeves has the excellent line that liberals can be concerned about both equality for women and the struggles of boys and men because both are justice issues that cry out for attention.

Reeves does a tremendous service in diagnosing the maladies that boys and men suffer, including the fact boys are falling behind girls in elementary and high school, are going to university proportionately less than young women, and are increasingly disengaged from the workforce and family life as they struggle to find meaning in a world that is seemingly leaving them behind. By no means is this true for all men, but true on average, and those that suffer the most are typically from lower income, lower education groups (one chapter is cleverly titled “Class Ceiling”).

Unfortunately, many of these problems become mutually reinforcing. As boys fall behind in schooling, it affects their employment opportunities and attractiveness to women seeking partners to marry. Reeves says, “with the rise in female earning power, men need to clear a higher bar to be seen as husband material.” In just one of the dizzying array of statistics, Reeves notes that “the marriage rate of men 40-44 with a high school education or less has dropped by more than 20 percentage points over the past 40 years, compared to just six percentage points for those with college education.” He quotes his colleague Isabel Sawhill who says, “Family formation is a new fault line in the American class structure.”

Reeves notes that many policy interventions, even ones not designed to specifically help women, often do not aid men. He calls for several reforms to help boys catch up in schools and for young men to enter university, to help fathers reconnect with their children, and attract men to the so-called healing professions (traditionally female occupations of teaching and nursing, two areas of employment that tend to be recession-proof and in which the U.S. faces creeping labour shortages). The proposal that is getting the most play is “redshirting” boys so that they start school one year later than girls by offering parents the chance to delay boys’ start of school to allow their slower developing brains to catch up to girls in their grades.

One area that a growing number of liberals and conservatives are agreeing on is making work more family friendly. Politicians like Justin Trudeau have taken up this cause as a way to give women a leg up in the workplace, but Reeves shows that doing so would also help men connect with their children. What the economist Claudia Goldin calls “greedy jobs” – careers that lucratively reward long and unpredictable hours – needs a “new ethos” (according to Reeves); “A job that requires a man to work long hours to make good money is not father-friendly, at least not in the way I think fatherhood must now be defined.” Fathers, Reeves correctly says, must do much more than fulfil a breadwinning role, which too often “does so at the price of his parenting role.” Reeves places a lot of stock in men finding meaning in family life as they increasingly are marginalized in the workplace.

There is much to applaud in Of Boys and Men. It is about time that liberals begin to take the plight of boys and men seriously, and Reeves has the credentials and platform to get the political Left to notice these issues. What is so annoying is that the book appears only written for the Left, as it generally ignores the work that conservatives have done on these issues and reduces conservatives’ concerns to a cartoonishly patriarchal caricature. He repeatedly downplays conservative concerns about boys and men as catering to culture war politics and dismisses any traditionalist arguments as a futile desire to “turn back the clock.”

One source that Reeves never mentions is Nicholas Eberstadt of the American Enterprise Institute, whose 2016 book Men Without Work speaks directly to many of the issues in Of Boys and Men, especially when Reeves describes how men are falling behind in remunerative and meaningful work, often by completely dropping out of the workforce. Eberstadt’s “post-pandemic edition” does not update the numbers in the main of the text but offers a new introduction that explains the employment situation for men since the first volume was released has gotten worse, noting “It seems that in just six years, America has gone from ‘men without work’ to ‘work without men’,” as there was 11 million job openings at the time of his update.

Using various data sets, Men Without Work describes the trend of fewer and fewer men working. Eberstadt correctly notes that labour force participation rates are more important than unemployment rates, as the former describes the number of men who are working or looking for work as a percentage of all prime age men. The unemployment rate measures the number of people looking for work as a percentage of people working or looking for work. Many men have simply dropped out of the workforce. Now about one out of three men of prime age are completely disengaged from the workforce. This is not healthy.

Using various data sets, Men Without Work describes the trend of fewer and fewer men working. Eberstadt correctly notes that labour force participation rates are more important than unemployment rates, as the former describes the number of men who are working or looking for work as a percentage of all prime age men. The unemployment rate measures the number of people looking for work as a percentage of people working or looking for work. Many men have simply dropped out of the workforce. Now about one out of three men of prime age are completely disengaged from the workforce. This is not healthy.

Eberstadt examines some of the reasons, and focuses on economics and government programs, as opposed to culture. He places the bulk of the blame on government programs that allow men to get by despite long-term escape from a paying job. In short, “the living expenses of un-working men today are subsidized by Uncle Sam.” He does not ignore the cultural impacts of unworking men, noting that they are spending more of their time in leisure activities and becoming disconnected from their communities. Eberstadt concludes that “this mass voluntary flight from work by men … lies at the center of so much of America’s new dysfunction and despair.” The retreat from work accompanied the retreat from family, promoted welfare dependency, “routinized the support of men by prime working age women,” and led to declines in social cohesion and social trust.

Among the fixes Eberstadt suggests are a “work first” principle in the provision of welfare, greater job training and education, work credits, and addressing the huge problem of previously incarcerated men fully rejoining society (“an ennobling moral goal for a forgiving people”).

Recognizing that boys and men are struggling with school, employment, and meaning, and addressing those problems, is itself an ennobling moral goal, and an urgent one. It is too bad that one of these authors decided to make it a partisan issue when addressing them will require a broad societal consensus.