Paul Tuns:

As everyone knows, the price of housing — both renting and buying a place to live — is skyrocketing across the country. The issue has seized politicians with the Trudeau budget introducing no less than 17 budget measures to address housing affordability and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland saying during her budget speech that out-of-control housing prices is an “intergenerational injustice.” Conservative leadership contender Pierre Poilievre is reaching a new cohort of younger voters by promising to make the dream of buying a house a reality for millennials (those born between 1981 and 1999) and Generation Z (those born between 2000 and 2009) by vowing to bring down housing prices by going after municipal restrictions that limit the supply of new residences. The reasons for rapidly rising housing costs are complex, but other than acknowledging the seeming unfairness of it all to a whole generation of young adults who are being priced out of homes, lost in the discussion are the individual and societal costs when people in their 20s and early 30s can no longer find a suitable, stable residence.

As everyone knows, the price of housing — both renting and buying a place to live — is skyrocketing across the country. The issue has seized politicians with the Trudeau budget introducing no less than 17 budget measures to address housing affordability and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland saying during her budget speech that out-of-control housing prices is an “intergenerational injustice.” Conservative leadership contender Pierre Poilievre is reaching a new cohort of younger voters by promising to make the dream of buying a house a reality for millennials (those born between 1981 and 1999) and Generation Z (those born between 2000 and 2009) by vowing to bring down housing prices by going after municipal restrictions that limit the supply of new residences. The reasons for rapidly rising housing costs are complex, but other than acknowledging the seeming unfairness of it all to a whole generation of young adults who are being priced out of homes, lost in the discussion are the individual and societal costs when people in their 20s and early 30s can no longer find a suitable, stable residence.

Housing bubble

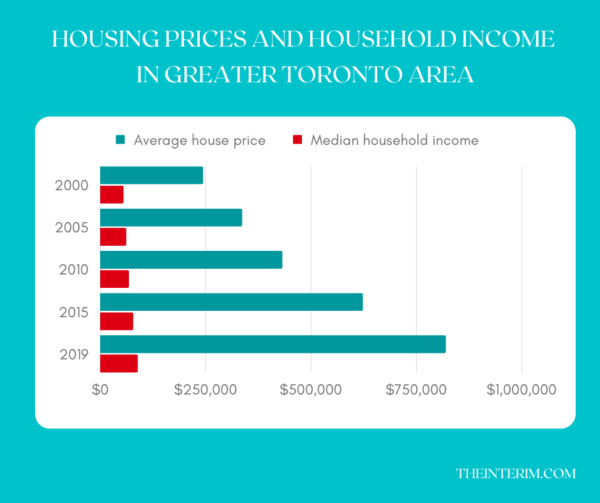

The figures are mind-boggling. There are a number of ways in which economists determine the strength of the housing market, but the easiest and most accurate is the Canadian Real Estate Association monthly report on selling prices, which represents the sales activities of more than 100,000 realtors. In February, the price of the average Canadian home sale price was $816,720, up 20 per cent compared to February 2021. It also marked the second busiest month of sales, with 58,209 homes changing hands. The 3.5 per cent increase in the selling price compared to January is the highest monthly jump on record.

Toronto and Vancouver skew the figures somewhat, with average home prices in the two markets north of $1.3 million; taking out those two municipalities brings down the national average nearly $180,00 to $636,000. Still, it would be incorrect to say that rapidly rising housing costs are limited only to these large cities. In Hamilton, Ont., the average selling price exceeded $1 million for the first time. The average selling price in every province except Saskatchewan is above $300,000, and the Prairie province is only slightly behind at just under $290,000. Smaller cities like Cape Breton, N.S.; Fredericton, N.B.; Kamloops, B.C.; Trois Rivieres, Quebec; and Woodstock, Ont., have all experienced increases in housing prices above 30 per cent over the past year, while Chilliwack, B.C. and North Bay, Ont., have seen selling prices rise by more than 40 per cent. Bancroft, Ont., just south of Algonquin Park, saw a February 2021 to February 2022 increase in housing selling prices of nearly 41 per cent, to over $514,000. Even in relatively stable housing markets like Brandon, Manitoba, and Sherbrooke, Quebec, saw selling prices increase between nine and 15 per cent.

There are a number of reasons for the torqued housing market: historically low interest rates that are only beginning to rise, numerous supply chain issues, more disposable income among potential home-buyers, pent up demand from young adults who were delaying entry into the housing market, and a desire to move to roomier abodes after the experience of two years of pandemic lockdowns. But these are only exacerbating already existing trends of steadily rising housing costs.

Even before the eye-popping February numbers were released, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a group of 38 large economies, issued a report that found since 2001, Canadian housing prices have risen quicker than anywhere else in the world: 375 per cent compared to an OECD average of 220 per cent and more than 100 percentage points higher than the United Kingdom (270 per cent) and the United States (226 per cent).

Priced out

Financial advisors say a family needs a household annual income of at least $225,000 to buy a home priced at $1 million. Environics Analytics says that the median household income — the number at which there are an even number of households above and below — in 2021 was $82,436, or about one-third the level needed to buy a home large enough to shelter a family of more than one child in many markets. Average household income tends to be slightly higher than median income, but that means it is being increased by high-income earners and that home ownership could be a contributing factor to wealth inequality as homes with single-earners or lower earners are unable to purchase homes.

Last month, Better Dwelling issued a report that said “the gap between home prices and disposable incomes has never been this wide” as “Home prices have persistently outpaced wages for this generation, and it’s not slowing,” with “home prices now rising over 10 times the rate of income.” Since 1975, home price growth outpaced income by 228 per cent and by 277 per cent since 2005, which means that the gap has been accelerating. But in the last year, the housing price growth was ten-and-a-half times larger than income growth, or 1500 per cent faster. These numbers are probably unsustainable but the housing market is increasingly a difficult one to break into.

A recent Scotia Bank poll of Canadians under 34 years of age found that 62 per cent are putting off plans to buy a home. In 2020, 20 per cent of all Canadians said they were delaying buying a home because of the rising price; today that number has more than doubled to 43 per cent. A December Re/Max report on home ownership, found that just 11.4 per cent of Canadians 18-34 own a home, down significantly from previous generations. A Sotheby’s International Realty survey of Canadians between the ages of 18 and 28 (so-called Generation Z), found that 80 per cent of them do not think they will be able to afford a home in the city of their choice due to escalating real-estate prices, while 70 per cent still say they hope to someday purchase a home. The three most common factors cited for not being able to afford a home according to Sotheby’s was the inability to save for a down payment on a house. Polling shows that childless couples are slightly more interested in alternatives to stand-alone homes such as smaller arrangements such as laneway or backyard residences, or co-owning a residence with other family members — not necessarily living arrangements conducive to having a family.

Family formation

While there has been plenty of commentary on the housing affordability crisis, there has been little exploration of what it means.

Over the past six decades, there has been plenty of research on the connection between home-ownership and family formation, and most studies indicate that there is a connection between purchasing a first home and other milestones in life such as marriage and having children. Different studies come to different conclusions about the specific direction of the relationship — does home ownership lead to having more children or does having more children lead to greater home ownership — but there is undoubtedly a link between stable housing and having a family.

Demographers have generally found a link between high rents or housing costs and lower fertility rates, with one study finding that women delay first births by three to four years in expensive housing markets, and another study suggesting that volatile housing-entry costs can also depress fertility. The relationship between home-ownership and fertility has been discovered in most western countries. A 2010 study in the Housing Studies journal examined ease of access to mortgages and found a correlation between a lack of access to mortgages and lower fertility. A 2012 study of Swedish families published in the Journal of Population Economics found that the link between family formation and entering the housing market was most robust for younger adults, that “the childbearing decision of these cohorts also seems to be more sensitive to changes in the user cost.” A study published last month in the journal Child Indicators Research summarizes the preponderance of the evidence: “Housing and childbearing trajectories are interlinked over the life course. Adequate housing is an important factor for fertility, residential migration often precedes childbearing and constraints that hamper residential migration can serve to delay or prevent family transitions.”

A 2021 study published in Demography, found that over the past 30 years in the United Kingdom, “the likelihood of becoming a parent has declined among homeowners, whereas childbearing rates among private renters have remained stable,” seemingly upending the established link although it is a bit of an outlier.

There are any number of theories for the connection between home ownership and family formation, but certainly the idea that home ownership brings stability factors into it. A 2014 study published in Social Work Research examined U.S. data from a survey of thousands of low-to-moderate income homeowners and found homeownership increased marriage stability and reduced rates of divorce among married homeowners. A 2013 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation study of low- and medium-income households found that home-owners reported feeling better about the well-being of their children, a greater feeling of stability, and a greater feeling of control.

Another factor in limiting fertility is the inability of families to afford moving to a larger house. Already stretched with mortgage payments for their starter homes, even as their first residence increases in value, other larger homes are increasing as well. In some cities, million-dollar “starter homes” are being advertised and many couples will be loathe to provide siblings for their first-born if they cannot afford a larger abode.

Social costs

It is not only family formation, however, that is affected by a generation being priced out of the housing market. A 2021 study published by the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA), “The Home Ownership Dividend of Canadians,” examined the non-financial benefits of owning a home for Canadians. The authors note that “Canadians may be familiar with the financial benefits that flow from homeownership, and the opportunity to build equity by paying into an affordable home for their families,” but that they are “less aware of the evidence that shows a wide range of civic, educational, health, and socio-cultural benefits to one’s family and the broader society.” Included among those benefits are higher test scores of children, food security, and community participation.” Economists call these “positive externalities,” the unintended good that is produced by goods and services.

Studies consistently find that people who own their own homes have greater self-reported feelings of happiness, life satisfaction, self-esteem and personal control. One study posited that home-ownership is a safety net that provides the requisite security to feel good on a number of measures; others suggest that “rootedness” and greater “agency” could be factors. Whatever the reasons for it, there is a well-established connection — and probably a causal one — between home-ownership and higher measures of life satisfaction, however it is gauged.

A 1999 study of German and U.S. homeownership by researchers at Harvard University “found there was a relationship between homeownership and pro-social activities such as home repair, yardwork, political participation, and volunteering.” A 2003 study in the Journal of Housing Research found higher rates of volunteering among homeowners than others. In 2009, a study of the German Socio-Economic Panel survey found that among immigrants, “homeownership helped support stronger national and community identification and a greater sense of connection and integration with their new country.” Studies show that homeownership correlates to higher voter turnout, especially at the local level. And a 2012 study in the American Journal of Community Psychology found that homeownership had a strong effect on local violent and property crime rates. The CREA concluded, “The rootedness of homeowners is a potential contributor to these positive civic outcomes: by virtue of their longer tenure and more stable financial situation, homeowners may be more inclined to invest into and participate in their neighbourhoods.”

An Angus Reid poll released last month found young adults do not feel as tied to their communities as do older adults. No doubt that is because they are not rooted by homeownership. People who are not attached to their communities will not become active to improve their neighbourhoods. And with homeownership comes responsibilities to repair (new coats of paint, fixing the roof); is it too much to suggest that the stability of a home could be a useful tonic to the ephemeral existence many young adults occupy online?

Solutions

We have a chronic problem of not building enough housing and most observers say we are about 1.5 million homes short of demand. The federal government’s target is to build just over 100,000 housing units over the next five years. At the same time, the federal government’s target for new immigrants over the next five years is 2 million people, which will only increase demand. Most government policies to address housing affordability are aimed at giving aid to homebuyers – which might only increase demand, thus driving up prices. Taxes on speculative investing will have only a minor effect on demand. Ultimately, policymakers must make it easier to build more residential units – single dwellings and higher density housing. Failing to do so will, as the research suggests, lead to greater problems than finding sufficient shelter for those who need it.