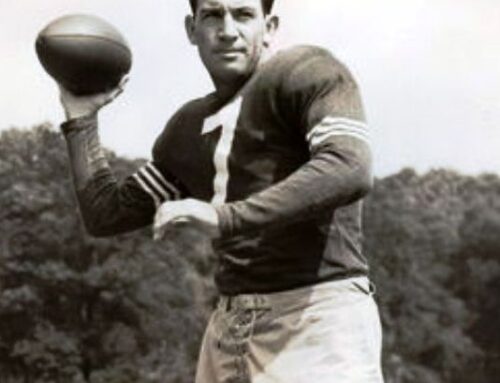

Fr. Ted Colleton dies at the age of 97

In the evening of April 26, Fr. Ted Colleton passed away peacefully in La Salle Manor in Toronto where he had been convalescing for four years. The pro-life movement lost one of its giants.

Edward Colleton was born in Dublin on July 20, 1913. Fr. Ted joked, “my mother was there at the time, so I wanted to be there with her.”

Born to Nicholas and Frances Colleton, in a family of six children, he grew up enjoying athletics and social activities over study, and had a strong interest in acting. He said if he hadn’t become a priest, he would have become an actor. But he was strongly influenced by the Holy Ghost fathers and felt called to the priesthood.

He entered the novitiate of the Spiritan (Holy Ghost) order at the age of 19. The day he took his first vows, he was summoned to visit his dying mother. When he arrived to see her, Frances Colleton opened her eyes and whispered five words: “Edward, be a good priest.” He returned to Kimmage, the Holy Ghost Fathers Missionary College, to take his vows and she died later that day. Seven years later, in 1940, he was ordained in the Spiritan (Holy Ghost) order.

In a tribute video to Fr. Ted created in anticipation of Fr. Ted leaving Canada in 2007 to return home to Ireland, his Spiritan colleague Fr. Gerald FitzGerald said, “for Ted, the priesthood was the most incredible gift any human begin could be given.”

Soon after his ordination, Fr. Ted was sent to British East Africa – now Kenya — where he served as a missionary for 30 years. He had a dispute with President Jomo Kenyatta in 1971 over the dictator’s criticism of Christian missionaries. Fr. Ted wrote a letter condemning Kenyatta’s comments, pointing out that missionaries were integral to the development of Kenya, and he arranged for the letter to be delivered through the president’s mother-in-law, who was a parishioner. The dictator’s thugs collected Fr. Ted and packed all his worldly possessions into a plastic backpack. At the airport before departing, he declared: “Ladies and gentlemen: I’m leaving your country after 30 years. I’m takes a shaving kit, the clothes I am wearing, and a Bible. I hope that everyone who comes to your country puts in as much and takes out as little.”

After a short return to Ireland and England, Fr. Ted was sent to Toronto to work with the Volunteer International Christian Service in Toronto to promote mission work abroad. But he would find a new mission for himself: promoting the Culture of Life.

During the homily at Fr. Ted’s funeral, Fr. Patrick Fitzpatrick joked that if Canadian immigration knew what mischief Fr. Ted would create once in Canada, they might not have let him in.

When he came to Canada in October 1971, abortion had been legal for two years. He was shocked. Fr. Ted spoke two African languages and said he never heard the word for abortion uttered in either one of them. It was, he said, unimaginable that the women of Kenya would voluntarily murder their children in the womb. He dedicated his life to protecting the unborn, telling Grace Petrasek, author of Silhouettes in the Snow: Profiles of Canadian Defenders of Life, that the “killing of unborn babies by the thousands … shocked me into action.” At the age of 59, when others would begin looking forward to retirement, Fr. Ted began a second career that would last more than 35 years as a pro-life activist.

Throughout the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, Fr. Ted spoke to classes, gave pro-life sermons, addressed conferences and meetings, carried out missions and retreats, wrote hundreds of columns, picketed abortuaries, and, as Campaign Life Coalition national president Jim Hughes told The Interim, “only stopped to pray.”

Hughes recalls talking to Fr. Ted not long before his 90th birthday, when the elderly priest lamented “I’m just not doing enough” and that “I don’t have the same energy I had.” Hughes asked him how many hours he had worked the previous week. Fr. Ted estimated he gave 80 hours to the cause.

Fr. Ted had the authority of a person who walks the walk. While he was a man of many words, Fr. Fitzpatrick noted, “but above all, a man whose words became flesh. He lived what he proclaimed.” Fr. Ted’s commitment to the cause was such that whatever he was doing was not enough. He was arrested more than a dozen times, including in December 1985 for padlocking the back gates to the illegal Morgentaler abortuary and charged with mischief. He said he had no choice but to take action against the illegal abortion mill because it was killing unborn babies. Awaiting trial he served six weeks in jail, but was ultimately exonerated when Provincial Court Judge Lorenzo DiCecco found him not guilty.

The incident earned him the media nickname “the Padlock Priest.” Just as he was persecuted by the authorities in Kenya for standing up on a matter of conviction, he was once again paying a penalty for taking a principled stand.

Fr. Ted was also a columnist for The Interim for more than 25 years beginning in its inaugural issue in March 1983. In 1987, Interim Publishing anthologized his columns in Yes, I’m a Radical. When he was arrested for his pro-life activities, some critics called him a radical. He embraced the description, using the epithet in the title of his book, which went on to sell 20,000 copies in multiple printings over two decades. In 1990, Fr. Ted penned an autobiography that focused on his time in Africa, but included his arrest and time in jail in Canada for his pro-life work. Yes, I’d do it Again, was also a bestseller and went through four printings. He concluded the book looking back as his career and the idea of the priesthood and ended with “I want to affirm this fact: if I had another life to live, I’d do it again.” A third book, I’m Still a Radical, was a second collection of columns. Taken together over 20 years, his books raised more than $1 million for the pro-life cause, mostly subsidizing The Interim through its early years.

The Interim inaugurated the Fr. Ted Colleton Essay Contest for high school students in 2001 in honour of his contribution to the movement and the newspaper.

Fr. Ted joined the board and worked as a volunteer with Birthright, assisting pregnant women who chose life. He later joined the board of Toronto Right to Life Association and became a member of their speaker’s bureau. Eventually, he joined Campaign Life Coalition. (He would also become a founding member of Priests for Life Canada and serve on the board of Business for Life.)

Jim Hughes said that Fr. Ted was among those who brought the future president of Campaign Life Coalition to the pro-life movement. Meanwhile, Fr. Ted said it was Jim Hughes who brought him to the political wing of the movement. Regardless of which version is correct, the two men had a great respect for each other, and worked together for more than three decades to oppose abortion. But the relationship went deeper than that. They were friends.

The two pro-life leaders lived a block apart and Fr. Ted would visit Hughes regularly, dropping by for dinner, dessert, or conversation. When Fr. Ted “retired” from active pro-life work, Hughes, along with Terry Blair tended to his needs at La Salle Manor. Hughes would drive him to various LifeChain events and said it was difficult to guess whose spirits were lifted more: Fr. Ted’s or those he met holding pro-life signs at the intersection.

“Fr. Ted was a giant of a man, a giant of a pro-lifer, who was one of the great heroes of the Canadian pro-life movement,” Hughes said. “He was a wonderful example, giving everything he had for the unborn and vulnerable.” But Hughes said Fr. Ted never thought it was enough. When Fr. Ted was living at La Salle Manor, a retirement home for priests and ministers, unable to get out much, and beginning to forget more than usual, he complained that he was unable to do much for the cause he served in active duty for 35 years. Hughes asked him if he still prayed, and Fr. Ted indignantly answered yes. Hughes reminded him that for more than three decades he told audiences that the most important thing they could do for the unborn was pray.

Fr. Ted had written that if he was ever bound to a wheelchair, he could at least pray for an end to abortion. He spent his days praying at La Salle Manor waiting to return to Ireland – a return that never occurred.

Fr. Ted is fondly recalled for his jokes and card tricks. What many people did not realize was that his humour and stories were theatrical opening acts. After the light-hearted introduction, he had audiences eating out of his hands, and as Fr. Fitzpatrick said in his homily, “he had given them much food for thought.”

Jim Hughes told The Interim that Fr. Ted provided spiritual nourishment for the pro-life movement for the best part of four decades, and that “not just the movement but all of Canada lost an inspirational leader and astounding example.”

It was Grace Petrasek who gave Fr. Ted the nickname the Lion in Winter. Drawing on his experience in Africa before coming to Canada, she explained in Silhouettes in the Snow that he was “viewed by pro-lifers as those of a roaring but lovable and tender-hearted lion.”

The roar might have been silenced, but his legacy lives on.

Fr. Ted was predeceased by his sister Nora, an actress and field hockey player, who died at the age of 18; Kathleen (Daly) and Sheila (Clancy) survived into old age; his younger sister Maeve, who died at the age of 18; and brother Nicholas, who was named after their father and died young.