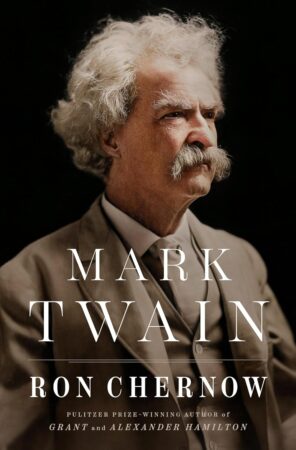

Mark Twain

Ron Chernow (Penguin, $60, 1174 pages)

Ron Chernow, biographer of J.P Morgan, Alexander Hamilton and Ulysses S. Grant, has turned his attention to the most American of authors, Mark Twain. Chernow describes Twain, born Samuel Clemons in 1835, and his search for fame and fortune in a thoroughly researched, rich, and brisk-moving 1100-page biography. Chernow says that Twain “thrust himself into the hurly-burly of American culture, capturing the wild, uproarious energy throbbing in the heartland” and it could be “fairly” said that Twain “invented our celebrity culture.” Unlike many of our current celebrities, Twain had genuine wit, charm, and talent for wordsmithery and he became what Chernow counts as “the most quotable man in American history.” (There is no shortage of Twain’s humour in Mark Twain.) Twain began working in newspapers as a printer’s apprentice at age 12, although he was soon writing articles. Twain had to write and speak constantly for fees to make up for earnings lost on get-rich-quick schemes that usually failed. He wrote tirelessly – claiming he could not “tolerate” sleep — and would go on to write some of the most enduring novels in U.S. literature centered on two rascally boys on the Mississippi, Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. Twain’s genius was writing in the vernacular, something new in the mid-18th century, giving “voice to the buried portion of the population.” Chernow writes of Huck Finn narrating, Twain showed “how expressive colloquial language could be.” Chernow says, “We hear Huck talking in the idiom of the heartland, in a voice so pure and natural that it grows artful.” Unfortunately, Huck uses the n-word about 200 times and the book is now “an almost insuperable problem for educators” due to politically correct fussiness. In another invention, Twain got rid of the omniscient narrator so readers could eavesdrop on the characters’ thoughts. Twain captured both the frontier life and mindset at a time when the United States was opening new westward vistas.

Ron Chernow, biographer of J.P Morgan, Alexander Hamilton and Ulysses S. Grant, has turned his attention to the most American of authors, Mark Twain. Chernow describes Twain, born Samuel Clemons in 1835, and his search for fame and fortune in a thoroughly researched, rich, and brisk-moving 1100-page biography. Chernow says that Twain “thrust himself into the hurly-burly of American culture, capturing the wild, uproarious energy throbbing in the heartland” and it could be “fairly” said that Twain “invented our celebrity culture.” Unlike many of our current celebrities, Twain had genuine wit, charm, and talent for wordsmithery and he became what Chernow counts as “the most quotable man in American history.” (There is no shortage of Twain’s humour in Mark Twain.) Twain began working in newspapers as a printer’s apprentice at age 12, although he was soon writing articles. Twain had to write and speak constantly for fees to make up for earnings lost on get-rich-quick schemes that usually failed. He wrote tirelessly – claiming he could not “tolerate” sleep — and would go on to write some of the most enduring novels in U.S. literature centered on two rascally boys on the Mississippi, Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. Twain’s genius was writing in the vernacular, something new in the mid-18th century, giving “voice to the buried portion of the population.” Chernow writes of Huck Finn narrating, Twain showed “how expressive colloquial language could be.” Chernow says, “We hear Huck talking in the idiom of the heartland, in a voice so pure and natural that it grows artful.” Unfortunately, Huck uses the n-word about 200 times and the book is now “an almost insuperable problem for educators” due to politically correct fussiness. In another invention, Twain got rid of the omniscient narrator so readers could eavesdrop on the characters’ thoughts. Twain captured both the frontier life and mindset at a time when the United States was opening new westward vistas.

Chernow deftly and sympathetically tackles Twain’s handling of the thorny issue of race in the character of Jim, Huck’s rafting companion, and the interplay of characters of different race. The humanism of Twain should be not overshadowed by the terminology in common use in the 1880s. More problematic, Chernow describes Twain’s grooming of teenage girls whilst he was in his 70s, although he suggests that nothing came of those relationships. There is no shortage of cringeworthy details of Twain’s life and yet Chernow succeeds in painting a positive picture of a man whose work, while widely known, is no longer widely read, without the biography’s sin of slipping into hagiography. Whatever Twain’s personal shortcomings, his enduring influence is worth acknowledging and as Chernow makes clear in his masterful biography, worth reading or rereading to better understand not merely an author, but a country.