Rick McGinnis:

Interim writer, Rick McGinnis, Amusements

If you were a fan, you might have experienced the death of singer Gordon Lightfoot last month in different ways depending on where you lived. Expressions of grief and mourning were a testament to his popularity on both sides of the 49th parallel and all over the world, but the tributes and reminiscences from Canada had an elegiac tone that revealed a more specific sense of loss – one tied up in a generation, and an understanding of Canadian nationalism that it seemed Lightfoot embodied.

Lightfoot, who began his career as a boy soprano in his hometown of Orillia, Ont., rose to fame as part of the early ‘60s folk boom before establishing himself as a singer/songwriter with hits like “Early Morning Rain,” “Sundown,” “If You Could Read My Mind” and “Beautiful.” An intensely private man, he built his success on a personal relationship with his audience that saw him touring almost constantly. He played what turned out to be his final concert in Winnipeg, in October of last year, and cancelled his 2023 concerts in April, less than a month before his death.

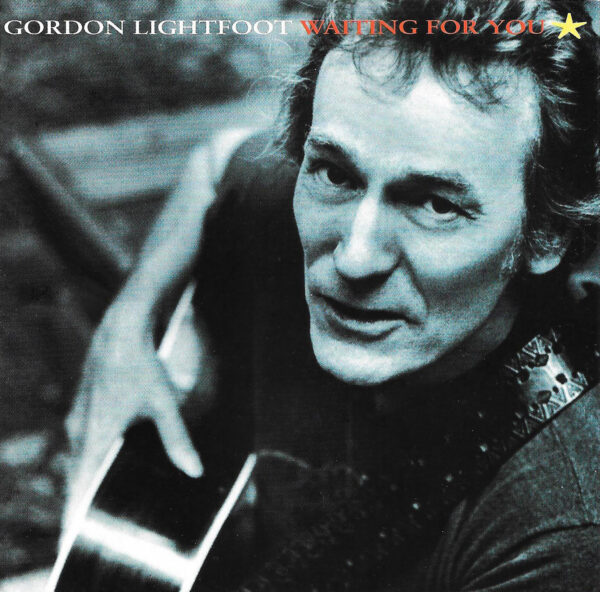

Lightfoot had every intention of going out while on the road; that much was clear to his fans, and it seemed obvious to me, years after my own brief personal connection to the man. I worked for Gordon Lightfoot as his photographer in the early to mid-‘90s, shooting an album cover (Waiting for You) and one of his legendary concerts at Toronto’s Massey Hall – a run of shows he played nearly annually starting with his first headlining gig there in 1967.

Lightfoot was a professional, unafraid to show how much work it took to do his job, and he expected the same commitment to that job from everyone who worked for him. I remember being told when I was hired how important punctuality and delivering results were, and in return Gord paid well, happily – and early, a rarity in my business, then and now.

Later in life he said that he was moving away from songwriting, as the effort required to produce songs – as well as record and tour – had taken a toll on his personal life that he no longer wanted to pay. (Lightfoot was married three times, and had six children with four different women, two of whom weren’t his wife.)

Gord’s aversion to talking about his personal life had made him a famously difficult interview subject, and I was anxious for weeks before our first shoot, afraid to overstep my new client’s personal boundaries, even accidentally. He would overcome this reticence in later life, opening up to Nicholas Jennings in 2017 for what was essentially an official biography (Lightfoot) and to the directors of a 2019 documentary, Gordon Lightfoot: If You Could Read My Mind.

Photograph of Gordon Lightfoot by Rick McGinnis.

But the word I’d choose to describe the man I worked with 30 years ago would be contrite. He let me know within the first few minutes of meeting him in his Rosedale home that it had been a decade since he’d had a drink; he was fit and lean, the puffiness of his hell-raising years in the ‘70s gone thanks to almost daily gym workouts, and married again with a child. I was taken aback by how candid he was about his circumstances, even more when he talked about the effort it took and his occasional moments of doubt while he drove me and my cameras back to the subway in one of his Cadillacs. I was getting more from Lightfoot than he was willing to volunteer to countless journalists and TV interviewers in the decades since he’d become a star.

In Lightfoot, Jennings writes that “ever since he’d quit drinking, making amends preoccupied Lightfoot. Sometimes he called it a process of atonement. Later he took to saying he was in a state of repentance. Either way, the duty weighed heavily on him.” Elsewhere in the book, discussing the song “Forgive Me Lord,” Jennings calls it:

“Almost Calvinistic in tone…the kind of repentant number churchgoers like his parents could appreciate. Lightfoot cites his ‘shame’ and ‘foolish pride’ and asks God to take his hand and lead him to salvation. And he makes the candid admission that he was ‘caught in the act,’ likely a reference to Brita’s adultery charge that she had found him in in bed with another woman. Although Lightfoot performed the song for years, the recording remained in the vaults until 1999, when it finally appeared on his Songbook box set.”

And Lightfoot took an active hand in pruning his repertoire when he lost sympathy with his original inspiration. When I was young, my favorite early Lightfoot tune was “Black Day in July,” a song about the 1967 Detroit riots that he introduced at a gig in the city a month after the riots by saying “This song is about your city. I’m sorry it has to be that way.”

But by the time I met him he’d dropped it from his sets, calling it “preachy” and saying that “I can’t be a politician; I’m not qualified to be a politician. The first thing that happens when you get involved is they stick a camera in your face, and as soon as they do that, I’m finished.” As much as I enjoyed the song, I couldn’t help but admire Lightfoot’s aversion to becoming a spokesman for political issues; he had very few explicitly political numbers in his repertoire, and fewer still lasted in his set lists.

Lightfoot was better known for his ballads, many of which were inspired by his admittedly messy personal life, and they were also subject to revision. He came to hate “For Lovin’ Me,” one of his earliest hits and a fan favorite, but he came to agree with his daughter Ingrid’s dislike of a song that, in a roundabout way, celebrated her father’s infidelities. “It’s as chauvinistic as hell,” Lightfoot later said, though he had much more pungent things to say about the song in the opening scene of the 2019 documentary.

Another song that came out of the breakup of his first marriage was “If You Could Read My Mind,” perhaps his greatest, though at the urging of his youngest daughter Meredith he eventually changed a line about “the feelings that you lack” to “the feelings that we lack,” admitting mutual culpability in the failure of that relationship years after it had ended. It might have ruffled a few fans’ feathers, but it’s hard not to admire an artist for acting on his own growth and sense of personal morality.

Tributes to Lightfoot after his death had a common theme: singer Ian Thomas compared him to the Group of Seven, and said that “I sensed our precious piece of this earth that we call Canada, in Gord’s songs.” Actor Kiefer Sutherland wrote that Lightfoot’s death meant that “Canada lost a part of itself;” and even an American like Billy Joel was moved to say that “His songs were the heart of Canada.”

This might have been hyperbole with anyone else, but it rang true for Lightfoot. When interviewed for Jennings’ book, I said that I had never felt more Canadian than when I walked behind a guitar-carrying Lightfoot down the path into the ravine behind his house. An avid hiker and canoeist who traveled the country extensively even while not on tour, his songs conveyed a sense of the vastness, natural beauty and brutal wilderness that’s both exhilarating and terrifying to anyone moved to travel outside of our cities.

Lightfoot’s vision of his country had enormous resonance to the generations old enough to remember Expo 67 and share in that watershed celebration of national unity, and he responded by writing songs like “Canadian Railroad Trilogy” – a bardic epic about the first railway to cross the country.

An early inspiration for his songwriting was a 1965 railway journey from Toronto to Moosonee that resulted in the song “Steel Rail Blues.” I took that same trip years after working with Lightfoot and found it just as inspirational as Gord did – a life-changing journey that I wish more Canadians could experience. But the segment from Toronto to Cochrane was shut down in 2012 and I had to fly to Timmins and drive to Cochrane. If Gord’s songs seem like period pieces sometimes, it’s because they’re written about a country that was once much easier – and cheaper – to explore.

Which is why I discerned an elegiac note in so many of the tributes to Lightfoot: the man embodied and admitted to failings, but his virtues – a genuine humility, a discomfort with the cult of celebrity, a sense of pride in his upbringing and sense of place – were very Canadian ones. Anyone with a lifetime sense of what Lightfoot lived through and sang about (I don’t remember Expo 67 but I can’t recall a time when his songs weren’t simply on the air.) must share a sinking feeling that his death took with him a cultural harmony that resonated for decades. He did more to define the country than any government program, and I don’t know what will take his place for anyone who didn’t share a time and place with him.