Paul Tuns, Review:

No One Left: Why the World Needs Children

by Paul Morland (Forum, $32, 264 pages)

Despite a growing number of countries experiencing rapidly declining fertility rates and falling natural population growth (that is, growth without immigration), there are still policymakers and thought leaders that insist that population growth is a problem. Paul Morland has been banging the drum on depopulation in numerous books and articles for decades. His latest No One Left is a clarion call to take urgent action to lift fertility rates.

Despite a growing number of countries experiencing rapidly declining fertility rates and falling natural population growth (that is, growth without immigration), there are still policymakers and thought leaders that insist that population growth is a problem. Paul Morland has been banging the drum on depopulation in numerous books and articles for decades. His latest No One Left is a clarion call to take urgent action to lift fertility rates.

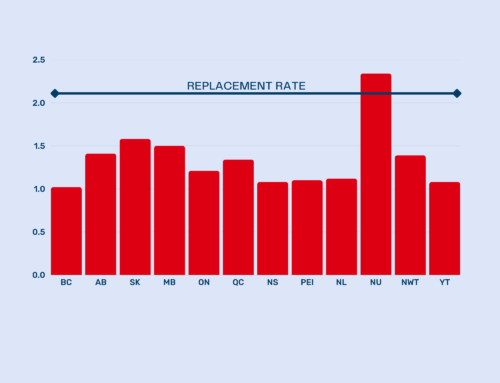

There are three stages to population decline: fertility rates fall below replacement levels (2.1 children per woman), then that is exacerbated by the subsequent smaller cohort of women of child-bearing age, and finally net decline because deaths exceed births while the country fails to attract enough immigrants for the population to continue growing. Some countries (Red China, for example), move directly from the first stage to the third stage; the shifts are often slow and subtle, then sudden. Population collapse can be seen decades in the making and then shock a country’s social and economic system with a sudden plummet in the number of people in the working-age cohort.

Policymakers blithely assume that immigration can goose population numbers indefinitely. That has been the working assumption in Canada and much of Europe, at least until recently. But Morland correctly observes that when the crisis of population decline is global in nature, as it suddenly has become, it is not possible that immigration can be a global solution. There are not enough Burundians to emigrate to Canada, the United States, China, Japan, South Korea, India, Europe, South America, and. Increasingly Africa itself.

Morland shows why rapidly declining fertility rates are a problem as country after country suffers economically and socially from smaller households, including but not limited to a decline in the number of consumers and workers. A major focus of Morland’s argument is that low fertility rates eventually lead to skewed dependency ratios – the number of workers supporting a country’s non-workers, mostly retirees – which threaten both economic productivity and a nation’s finances. Much of the welfare state in the west, including old-age pensions, was created when there were five or more workers for every retiree; in much of the developed world, the ratio has fallen to four or three workers for every two retirees, and some countries such as Japan and Italy are expected for have one worker for every pensioner by the end of the century. This is unsustainable.

Policymakers rely on immigration to ensure that the dependency ratio does not become too skewed in favour of seniors, but Morland goes to great lengths to show that such policies are often only temporary solutions and are not without their drawbacks (including social cohesion).

What can be done? Is it too late to do anything?

Morland points out that it is difficult to grow population naturally once it hits crisis levels of decline because the cohort of women of child-bearing age is simply too small. But policies and cultural attitudes must change immediately to incentivize families today to have more children so the next generation has a chance at sustaining healthy population growth.

The most important issue is changing expectations, so that family formation is a goal of young people. That is hard to do when a population is aging because markets and governments will respond to the growing number of elderly in everything from social programs (and the tax rates to support them) to urban and product design.

Morland recognizes that the few outliers in terms of fertility rates tend to be pockets of population of the Abrahamic faiths (Christianity, Judaism, Islam) although having larger Muslim or Catholic populations does not guarantee population growth (see Italy, for example). But as societies secularize, religion plays a lessened role for the next generation and its fertility-boosting benefits (among other benefits) will be missing.

Morland also argues that reviving fertility rates will not necessarily hurt the environment, noting that mankind’s imprint on the land has become more efficient as modern technologies and density (urbanization) lead to greater efficiencies in the use of the Earth’s resources. Anyway, what use is saving the planet if there are no people left to enjoy it?

Morland warns that “culture, like business, relies on new blood.” Human flourishing, not merely human existence, depends on reviving fertility rates. May Morland’s No One Left be a catalyst for political, religious, business, and cultural leaders to take urgent action to help boost the number of new humans.