Paul Tuns:

In late March, just nine months after Canada reached a population of 40 million, the number of people calling Canada home exceeded 41 million according to Statistic Canada’s live population tracker, with most growth coming through immigration.

In late March, just nine months after Canada reached a population of 40 million, the number of people calling Canada home exceeded 41 million according to Statistic Canada’s live population tracker, with most growth coming through immigration.

Statistics Canada reported that in 2023, Canada added 1,271,872 total inhabitants, a population increase of 3.2 per cent, the highest such figure since 1957. Most of that growth was a result of immigration, both permanent and temporary, accounting for two-thirds of the population increase.

Most temporary immigrants are students and temporary workers, and in recent months the federal government has said it will try to reduce the number of temporary residents, which economists say is partially responsible for the housing affordability crisis.

Last month, the Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey figures suggested that the number of people aged 15 and older increased by 411,000 in the first quarter of 2024, nearly 50 per cent higher than over the same quarter in 2023, and up from 241,000 in the last quarter of 2023.

In August 2023, CIBC Capital Markets released a report stating that official statistics undercount the total number of non-permanent residents (NPR). Benjamin Tal, an economist with CIBC, noted that the census data and the quarterly estimates were at odds, with the census missed nearly 200,000 NPRs, or about 20 per cent of the total. Furthermore, there is no count of students or workers who overstay their visas, and CIBC estimates that between 2017 and 2022, at least 750,000 NPRs stayed after their visas expired.

Tal said official planning for zoning, housing starts, social services, and infrastructure are affected by the uncounted workers and students staying in Canada.

NPRs are also drastically refashioning Canada’s demography. According to Statistics Canada, there are more temporary workers and students (2.2 million) than indigenous people (1.8 million).

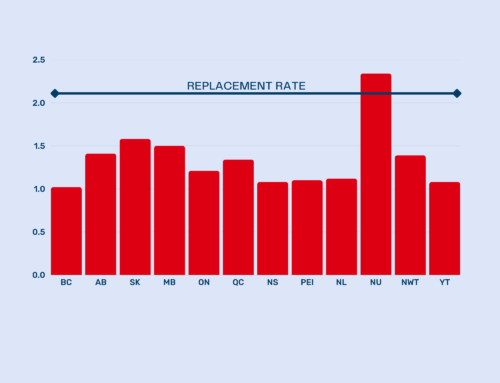

While Canada’s population has increased quickly, in January, Statistics Canada reported that the total fertility rate – the number of children born per woman of child-bearing age – reached its “lowest recorded” level in “more than a century of data” at a mere 1.33 children. A fertility rate of 2.1 is considered the natural replacement rate for a country.

When John Ibbitson and Darrell Bricker’s book Empty Planet was released in 2019 warning of declining fertility rates, Canada’s fertility rate was 1.51. When Stats Can released its latest figures, Ibbitson, a columnist for the Globe and Mail, wrote “to go from (1.51) to 1.33 in less than five years is remarkable.”

According to Statistics Canada, the five lowest fertility rates from 1921 to 2022 were in the five most recent years: 2022 (1.33), 2020 (1.41), 2021 (1.44), 2019 (1.47) and 2018 (1.51). Statistics Canada described those five years as “relatively volatile … with an initial large downward swing, then an increase, followed by another drop,” but continuing the long-term trend of decreasing fertility.

Statistics Canada also reports that “fertility rates decreased in all age groups of women less than 40,” the prime child-bearing age for Canadian women. Statistics Canada reported that the annual decline of -7.4 per cent from 2021 to 2022 was the largest decline since 1971-1972 (-7.6 per cent) shortly after abortion and contraception were legalized in 1969. Among wealthy countries, Canada had the third largest dip on fertility rates in 2022, following Netherlands (-8.4 per cent) and Germany (-7.7 per cent).

Fertility rates starkly differ among provinces, with B.C. at the low end at 1.11 children and Ontario at 1.27, while Alberta and Quebec have fertility rates of 1.45 and 1.49 respectively.