Oromocto is a vibrant, progressive New Brunswick town of 9,000, 20 kilometres from Fredericton and the home of Canadian Forces Base Gagetown. “Canada’s model town,” the chamber of commerce calls it.The chamber can list a new “service”: abortions at Oromocto Public Hospital.

Abortion activities formerly carried out in Fredericton’s Dr. Everett Chalmers Hospital are to move to OPH. It will become the main hospital site for abortions in Health Region 3, a large area extending north along the St. John River and deep into the centre of the province. The Morgentaler Clinic will still operate in Fredericton.

All the health facilities in Region 3 are under one governing body, so doctors with privileges to work in the region can move their activities from one facility to another with relative ease.

To some, moving from Chalmers seems like a good use of resources. Abortions can tie up operating rooms needed for other surgeries. OPH already is the locale for most of the region’s day surgeries, explains Shelley Fletcher, director of communications for the Health Authority.

She considers abortion medically necessary. But most are “abortion on demand,” says Peter Ryan, director of New Brunswick Right to Life and president of Campaign Life Coalition New Brunswick. He added that a January 2003 Omnifacts poll found 76 per cent of New Brunswickers oppose abortion on demand.

Ryan is concerned that this change could lead to Oromocto becoming the abortion capital of the province. If the Morgentaler clinic should close, OPH could be doing over 1,100 abortions a year.

The community had no say in this move, which affects them in many ways. “Terminating unwanted babies is not health care and should not be imposed on a community against its will,” says Ryan.

Like many residents, Chet Randall of Oromocto’s Knights of Columbus believes this will taint the community’s reputation. He is concerned about the implications for hospital staff who are conscientious objectors, and he thinks a hospital that performs abortion is in a conflict of interest.

In a letter to The Daily Gleaner, Norman Woodworth, Pastor of Oromocto Baptist Church, pointed out the irony of an abortion centre sending its soldiers around the world to save the lives of men, women and children. “No matter what the Supreme Court says, we all know that little life in the womb is a baby. Maybe we should be keeping our soldiers at home,” he suggested.

He pointed to further irony in Premier Bernard Lord’s musing about re-introducing the baby bonus to help stem New Brunswick’s dropping population. “Since 1969, well over 20,000 children have been aborted in this little province. Why not let our children live??”

New Brunswick sees about 1,100 abortions committed a year, 82 per cent of them in Region 3 (at Fredericton’s Morgentaler abortuary and Chalmers Hospital), with the rest scattered through the remaining seven health regions.

This prompted Ryan to pose the following questions in The Gleaner: Are all 900 of these medically necessary? If so, why do the women of Region 3 have so many more health problems than women in the province’s seven other health regions combined? Are some physicians abusing the system? Or are women having abortions mainly because of unwanted pregnancies (abortion on demand)?

Woodworth’s letter pointed out that declaring abortion medically necessary when it isn’t would be violating the laws concerning use of medicare funds. Abortion on demand would be using medicare money for birth control, Ryan says, and if there are this many genuine health problems, there should be an investigation to find out why women of this region have so much ill health.

Fr. Gerry Laskey, Anglican pastor of Gagetown, recalls that when community hospitals were run locally, the directors were responsive to the sensitivities and concerns of the community. Now that the geographical area covered is much larger, the directors come from much farther away and have much less contact with, or sensitivity to, the other communities. Since it’s no longer a “face to face” situation, it’s easier to simply make business-type decisions.

Fortunately, in this case, Health Authority chair Ross Giberson is also mayor of Oromocto.

Both Ryan and Laskey think there is good reason to be concerned about this new development. Laskey points out that people find it hard to picket their hospital because they have so many connections with it, from employment to personal and family health, and because its activities are so diverse. It’s often easier to picket a one-issue establishment like the Morgentaler clinic.

Both Ryan and Laskey think there is good reason to be concerned about this new development. Laskey points out that people find it hard to picket their hospital because they have so many connections with it, from employment to personal and family health, and because its activities are so diverse. It’s often easier to picket a one-issue establishment like the Morgentaler clinic.

Ryan encourages appeals to the Health Authority, as well as contact with local politicians. “There are many ways to get involved,” says Laskey, “including personal support for women in trouble. They can all make a difference.”

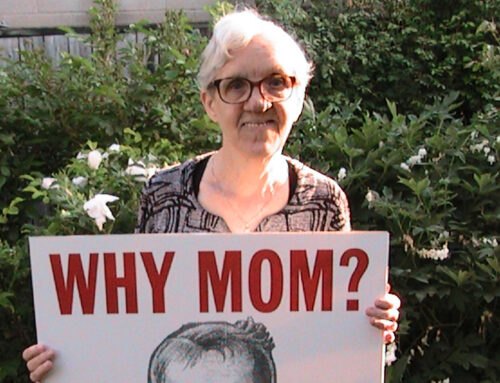

A large pre-Christmas rally and motorcade expressed community concern. Provincial MLA Jody Carr attended, saying he supported the effort and is personally opposed to unnecessary abortion. Poster messages included: “Peace on earth and in the womb,” and “What if Mary had aborted Jesus?” The ongoing rallying cry is, “Hospitals are for saving lives, not taking them.”