Emma Castellino

Review:

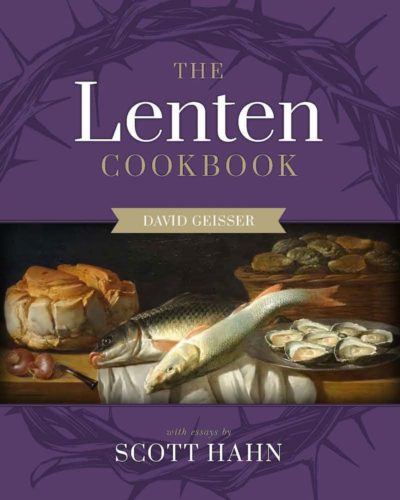

The Lenten Cookbook by David Geisser with essays by Scott Hahn (Sophia Institute Press, $29.95, 224 pages)

In the Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy, set in medieval Norway, we are told about one nursing mother who was exempted from her Lenten obligations. She took her accommodations just as seriously as she had previously observed the fast, and thrived. I was struck by how she did not interpret piety as defined by her sacrifices, but by obedience to her parish priest. It seems difficult now, as so little is required of us, to tread such a simple balance between legalism and laxity.

In the Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy, set in medieval Norway, we are told about one nursing mother who was exempted from her Lenten obligations. She took her accommodations just as seriously as she had previously observed the fast, and thrived. I was struck by how she did not interpret piety as defined by her sacrifices, but by obedience to her parish priest. It seems difficult now, as so little is required of us, to tread such a simple balance between legalism and laxity.

Scott Hahn introduces The Lenten Cookbook with a series of essays on the history and theology of Christian fasting. Hahn is a wonderful writer, and his personal joy in the practice is evident throughout. He is not heavy-handed about “liturgical living,” but manages to render our sacrificial traditions truly attractive in a secular culture.

A particular relief to my hard heart is Hahn’s context for the Church’s “relaxation” of fasting requirements in 1966. We find that not only are we not released from difficult practices, but we in the first world are called to abstain from some food at certain times. Certain fasts were, prior to 1966, binding under pain of mortal sin. This was relaxed by Pope St. Paul VI so that the poor need not suffer further denial but be free to sacrifice through prayer. However, his primary reasoning was so that the affluent might witness with even more material ascesis to the prior requirements, according to the widening wealth disparity at the time. We might take note that little of this trend has slowed.

Whether or not these ideas have worked out is a different story, I suppose, but it was beautiful to learn what was behind it.

I must admit that at the time of writing, I have only tried to make one of David Geisser’s recipes; but then again, it is not yet Lent; but then again, meat prices have risen so significantly that it might as well always be! It was an eggplant salad, which was very tasty if aesthetically unappealing. I take the blame, however, as I have not yet figured out how to cook an eggplant without it disintegrating.

We know that creativity thrives with more limitations. When I can make what I want for supper, I flounder. I found myself disappointed as I read through Geisser’s recipes, as if it were no more than another vegetarian cookbook. I wanted it to be a cookbook for the Black Fast, for a dwindling winter storehouse, for a world without a global harvest. The recipes seemed either too basic (4 different ways to have yogurt and muesli – but who needs breakfast when you’re fasting until noon) or too fancy (beluga lentils, but substitute red if you must).

Hahn describes the phenomenon of Irma Rombauer’s 1931 Joy of Cooking, which pumped blood back into the veins of America’s home chefs in the heart of the Great Depression. He hopes that this cookbook will likewise encourage joy in fasting, in an age where it is not obvious why – or how – to do it. I treasure my own copy of Rombauer’s book which, despite my personal inclination not to make or even look at an aspic (what were those all about?), contains such a wealth of basic practice that it transcends preference.

My reservations about the cookbook section are certainly not based on my own likes and dislikes; as with any collection of recipes there are dishes that look more doable or delicious than others. Certain tantalizing soups will surely go into rotation. However, in a way that would not have mattered if it had been “just” a cookbook, these recipes seem more of an appendix than a continuation of Hahn’s proposal. For example, the cookbooks released by the restaurant Joe Beef pursue comparable ideals. Joe Beef’s authors are not being pretentious, but it is at least a provocation to title one’s cookbook The Art of Living. And, indeed, we find out not only how to make marrow cultivateur, but why.

Then again, perhaps Fried Tofu, page 117, says it all: “He who wishes to find Jesus should seek Him, not in the delights and pleasures of the world, but in mortification of the senses” (St. Alphonsus Liguori).

Emma Castellino, a regular contributor to The Interim, lives in Hamilton, Ont., with her husband and two children.