Paul Tuns:

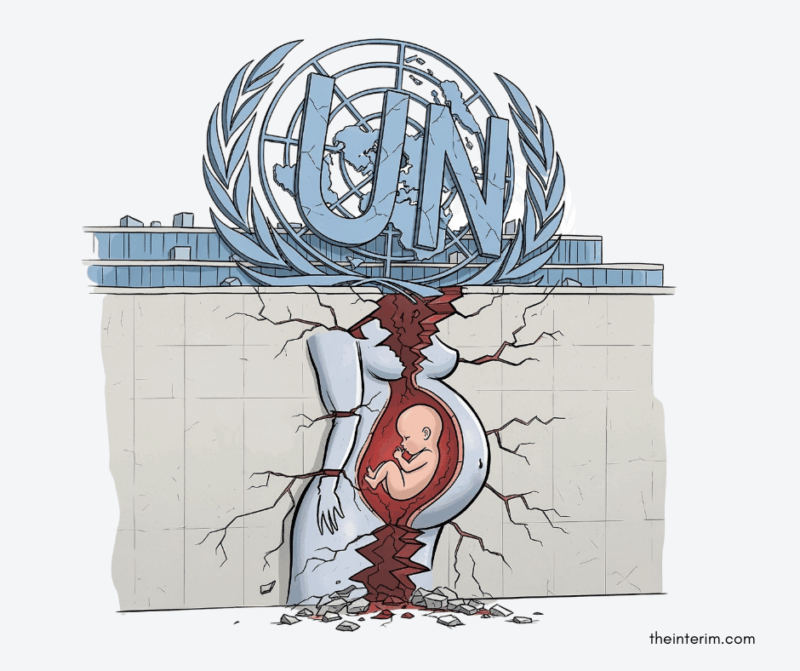

After the League of Nations disintegrated in the wake of World War II, U.S. President Frank Delano Roosevelt proposed the idea of the Four Powers (the U.S., U.K., Russia, and Red China) as an international body to coordinate cooperation among them. Throughout the war the idea morphed into what became the April 1945 San Francisco United Nations Conference on International Organizations. Over the next few months, delegates from 50 countries hammered out a charter, and the United Nations officially came into existence on Oct. 24, 1945 with 51 countries as inaugural members. The first meeting of the General Assembly and Security Council took place in January 1946. (The headquarters would move to New York in 1952.)

The United Nations was founded to coordinate and “harmonize” international action among member states to promote the peaceful adjudication of territorial disputes, and was not necessarily originally designed to address the domestic affairs of countries. In its first year, the UN created the UN Economic and Social Council which would promote the dignity of every individual while ostensibly respecting national sovereignty. The idea behind UNESCO was that peace and security must be built on the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind through education, science, and culture. UNESCO would soon create the Commission on the Status of Women to focus on women’s issues and created the Human Rights Commission to promote human rights. In 1948, under the auspices of UNESCO, the UN adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Article 3 of the Declaration stated, “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person,” before enlisting a broad range of positive rights such as social security and an adequate standard of living. The economist F.A. Hayek warned in an essay, “Justice and Individual Rights,” that guarantees of social justice with its focus on “positive rights” provided by the state or supernational agency, opened the door to infringements on liberty and coerced redistribution.

Over the next few decades, the United Nations as a guarantor of peace and security would be tested in conflicts in Africa, the Korean peninsula, Vietnam, and the Middle East. It would not be until the 1960s that Hayek’s warnings about positive rights would prove prescient in the fields of life and family policy.

In 1961, the UN held its First World Population Conference in Cairo. The Commission on the Status of Women promoted birth control as part of its model for third world development, the idea being that if women were “empowered” to have the number of children they wanted and spaced accordingly, burgeoning populations in Africa, Latin America, and Asia would be less of a strain on the world’s distribution of resources. But as Steven Jensen wrote in The Making of International Human Rights: The 1960s, Decolonization, and the Reconstruction of Global Values (2016) articulating access to education and health care, family welfare, and economic security – all of which included a component of “reproductive health and rights” – were part of the reframing of the human rights project in the 1960s. These rights were not merely “negative rights,” free of government coercion, but positive rights that required government intervention.

As the decade went on, growing fears in Europe, Canada, and the United States of burgeoning population in the global south were becoming mainstream. Already in the 1950s, non-government organizations such as the Rockefeller Foundation-funded Population Council, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), and Marie Stopes International, were promoting abortion and contraception to limit population growth in the developing world. IPPF and the Population Council were active in Red China, India, and Egypt, training medical students and activists to promote abortion and “family planning.” In her book Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control (2016), Betsy Hartmann reported that in India, Kenya, and the Philippines, many family planning interventions were coerced, including abortion, forced sterilizations, and birth control without proper information.

In 1965, the UN held its Second World Population Conference in Belgrade with the population “explosion” gathering greater urgency. The Trust Fund for Population Activities was established, which would pay for population-control efforts and by the end of the decade it was operating in 30 countries. In 1969, the United Nations Development Program, intended to promote the economic and social development of what was then called The Third World, became the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and focuses on controlling population as the means by which to achieve development in those countries. It promoted what it called “modern” families, by which it meant small families, preferably with only one or two children. Many western countries funneled their foreign aid through NGOs and UN agencies that were promoting, and sometimes foisting, abortion and family planning in the developing world. Mark Mazower, in his book Governing the World: The History of an Idea (2012), described the UNFPA as a front for the Population Council and argued that as a self-governing agency of the UN, it was not scrutinized by the General Assembly or its members states.

In 1968, delegates at the UN Conference on Human Rights in Tehran, explicitly tied population control to protecting human rights, with the Final Act document stating, “the present rate of population growth in some areas of the world hampers the struggle against hunger and poverty,” thereby “impairing (the) full realization of human rights.”

At the same time, countries from the Middle East, southeast Asia, Latin America, and parts of Africa were pushing back on what they saw as ideological imperialism with western technologies such as the inter uterine device and the contraceptive pill being foisted upon girls and families in their countries. NGOs such as Planned Parenthood, Marie Stopes, and the Population Council trained activists who would speak “for” women in the developing world while western delegates at these international meetings would ignore the national governments that did represent those women.

In 1966, the Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women adopted concepts and language from western feminism that questioned gender roles in the family and even the importance of family itself, focused on emancipating women from patriarchal systems. It routinely highlights abortion, and family planning was central to that project. Pro-family and religious groups from the developing world charge that this focus politicizes family life. 13 years later, in 1979, the UN created the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women – CEDAW – that holds regular sessions investigating discrimination in member states. To this day, it routinely criticizes the pro-life laws and regulations of countries that protect preborn babies.

In 1968, Helvi Sipila, the Women’s Commission chairman, issued her first interim report, placing family planning within the contest of women’s liberation, a first for a formal document of the United Nations.

In 1972, the UNFPA, United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund, World Health Organization, and World Bank established the Human Reproduction Special Program (HRP) to promote research and training in “human reproduction,” a euphemism for family planning through abortion and contraception. In an important move, the Section on the Status of Women was moved from the Human Rights division of the UN to its development wing, once again intermingling family planning with economic and social advancement.

UNICEF had denied supporting family planning or population control, but from at least 1966, there were line items for funding family planning programs, and the UNFPA provided monies for UNICEF projects. Henry Labouisse, UNICEF’s executive director in 1972, said the organization was concerned about the “population explosion” and claimed “it is the children who suffer most from the inability of parents to provide sufficient care and attention to their large families.” In 1970, it was later reported by then Interim columnist Winifride Prestwich in UNICEF: Guilty as Charged, that UNICEF was providing contraceptives to parents and by 1974 was distributing propaganda encouraging families to limit the number of children they had to two. Prestwich reported that by the end of the decade, “about 80 per cent of the (oral) contraceptives funded by the United Nations Fund for Population Activities are purchased by the United Nations Children’s Fund.”

The World Population Conference in 1974 was held in Bucharest. It promoted sex education and depopulation although the World Population Plan removes references to specific lower population targets. G-77, a group of 77 countries from the developing world were vocal in opposing the neo-Malthusian idea that growing population slowed economic development, arguing, instead, that slow economic development led to rapid population growth. More than one intervention said that “development is the best contraceptive.” Yet at least two-thirds of these countries had active population control or family planning regimes in place.

Sipila would state in a report that same year that the “status of women,” “population change,” and “third world development” were interrelated. Nearly all UN agencies, including the Food and Agricultural Organization and the International Labor Organization, would come out in support of family planning and use their various auspices to promote the practice; the FAO would distribute condoms in the developing world in its packages of powdered milk and cartons of grain while the ILO established a “family limitation mandate” which promoted family planning information in worker resource packages and employee compensation agreements.

Where national governments were not open to adopting anti-life and anti-family policies, UN representatives would work with NGOs on the ground to promote abortion, contraception, and sex education. Sipila would hold such meetings in Kenya, the Dominican Republic, and Indonesia in 1971 and 1972 alone. In 1972, Sipila admitted that at least one local NGO complained that “many family planning programs have failed to ask women what they want.”

This thinking would permeate the United Nations for the next two decades, including at the International Conference on Population in Mexico City in 1984, in which the final document promoted “safe and effective family planning methods,” although it did not state what methods that might include. It was in reaction to this conference that U.S. President Ronald Reagan signed the Mexico City executive order prohibiting U.S. money from being used to pay for or promote abortion globally. Since Reagan, every Republican president (George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, Donald Trump) has also signed executive orders prohibiting U.S. funds to pay for or promote abortion globally, while each Democrat president (Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Joe Biden) has rescinded those orders.

Although it denied its support of China’s one-child policy and its enforcement through coerced abortion and sterilization, in the 1990s, it was widely reported that UNICEF supported the policy. The UNFPA would also deny its involvement with China’s one-child policy although it would eventually be revealed that the Fund gave China $50 million in 1979 to launch the Chinese State Family Planning Commission, which was responsible for implementing the one-child policy. The UNFPA would often praise China’s efforts to slow its population growth and would later assist Vietnam with the development of its two-child policy.

At the Earth Summit in 1991 in Rio de Janeiro, countries committed to “sustainable development” and the idea that population growth itself was an environmental problem. It was the first in a series of large, international conferences that promoted population control and family planning as central to their large themes: the Population and Development Conference in Cairo (1994), the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995), Habitat II on Human Settlements (housing) Conference in Istanbul (1996).

As the Beijing Conference on Women approached and U.S. First Lady Hillary Clinton made it clear that the United States would push the idea of abortion as a universal human right, the Holy See called upon all Christians to oppose it. Answering the call to stand athwart the forces of abortion, Campaign Life Coalition sent a delegation to Beijing headed by Louie Di Rocco to support pro-life delegates in opposition to efforts to recognize a “right” to abortion. CLC would send delegates to future conferences, and United Nations officials began complaining about the organizational power of pro-life NGOs, including CLC and the World Youth Alliance, despite there being about 100 times more pro-abortion NGOs operating at these meetings.

In 1997, the UNFPA released a document, “The Right to Reproductive and Sexual Health,” which outlined the development of “a human-rights approach to reproductive health” and its evolution from “the right of family planning” to the “affirmation” of the “right” to “better sexual and reproductive health.” The document was a response to the Cairo and Beijing conferences.

When developing the Sustainable Development Goals, the Millennium Summit (2000) promoted “reproductive health and rights” as part of Sustainable Development Goals managing global social development.

Obianuju “Uju” Ekeocha of Culture of Life Africa, reported in 2019 that in 1993, the year before the Cairo conference, total aid spending for family planning and depopulation through the UN and direct assistance from countries was $610 million. By 2012, “the total funding allocated to the same cause had been increased to a staggering $12.4 billion,” a nearly 2000 per cent increase. Over the same time frame, total foreign aid to developing countries rose 138 per cent from $56 billion to $133 billion. Ekeocha also reported that while more foreign aid was given for education, water, sanitation, healthcare, and civil society than for family planning in the early 1990s, that since 2009 “population-program funding has surpassed funding for everything else within this sector.”

While western delegates and feminist NGOs have tried repeatedly – and failed — to get abortion declared a human right, it has successfully made abortion a central component of “sexual and reproductive health and rights.” Today the United Nations claims, “The rights of women and girls to the highest attainable standards of health, including sexual and reproductive health, are firmly grounded in international and regional human rights instruments” and that “these rights have been reaffirmed in consensus agreements established during the International Conference on Population and Development, the Beijing Platform for Action and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and recognized by international, regional and national human rights mechanisms and jurisprudence.” Thus, the UN Secretariat maintains, “This means that States have obligations to respect, protect and fulfill rights related to women’s and girls’ sexual and reproductive health.”

Insulated from public opinion of members states and accountable to no one but the delegates of members states, UN bureaucrats, buttressed by left-wing activist NGOs, have moved more recently to pushing sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) ideology. The first reference to SOGI was read into the record by the Norwegian delegation in 2008 and referenced by bureaucrats in debate during various meetings, but it was not until 2011 that the UN Human Rights Council called upon the Human Rights Commission to study discriminatory laws and practices against individuals based on SOGI. Five years later, the renamed Commission — the UN Human Rights Council — created the Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on SOGI that would file reports on supposed rights violations.

Also, during meetings on development, women’s rights, and children’s rights, feminist NGOs and UN bureaucrats push comprehensive sex education that is often at odds with traditionalist societies in Catholic Latin America, primitive Africa, and majority-Muslim countries in northern Africa and Asia.

In an interview with The Interim (published in this edition), Campaign Life Coalition vice president Matthew Wojciechowski says, “Pro-lifers want the UN to return to its founding principles: a forum where member states collaborate to improve the quality of life for every human being and promote global peace.” But perhaps the abortion ideology permeates the United Nations too deeply.