Rick McGinnis

There’s an uncommon moment recalled in Norman Lebrecht’s bitter but celebratory 2007 book The Life and Death of Classical Music where the classical music industry, such as it had existed for just over a century, finally died. It was a dinner in a London restaurant in December of 2004, a small retirement party given for Peter Alward, the head of EMI Classics, by Costa Pilavachi, his opposite number at Decca Records’ classical music division.

After years of steeply declining sales and the corporate amalgamation of what were once a half dozen competing major record labels, the writing was on the wall. Singers, soloists, string quartets, conductors, and orchestras who had relied on record sales for their existence were being cut loose by label executives with an eye on the shrinking bottom line. Record executives like Alward (Pilavachi would leave Decca a year later) whose long careers were a balancing act between art and commerce, understood that it was time to make a graceful exit. “There was no rancour and few regrets,” writes Lebrecht, who was a guest at the dinner. “Most around the table had done their bit to keep the art alive. Nobody wanted it to end this way, but all things in life are finite and the act of closure is, of itself, cause for celebration.”

It didn’t mean that there was no more classical music. Centuries of compositions and a hundred-plus years of recordings weren’t going away, but the audiences who listened to them were apparently ageing and disappearing, and the musicians who insisted on trying to make a living performing it had become little different than their rock music counterparts playing bars and clubs and little concert venues and the occasional festival – eking out a living on ticket sales, merchandise, fundraising events, online crowdfunding and the rare charitable angel willing to underwrite their effort, for a price that sometimes meant playing a party, backing a dilettante soloist, or performing material they would have once dismissed as sub-par, under the outsized logo of some corporate entity.

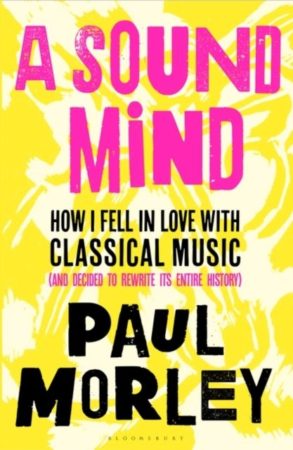

This is where Paul Morley comes in, with his new book A Sound Mind. Like Lebrecht, Morley is a British writer who specializes in music, though Morley began his career with the punk rock explosion in the late ‘70s, and briefly crossed the aisle in the early ‘80s by partnering with musician Trevor Horn (of The Buggles fame) on a record label (Zang Tumb Tuum, home of Frankie Goes To Hollywood) and as the “non-singing lead vocalist” of the label’s house band, Art of Noise.

As the new millennium shuffled into its second decade, Morley realized that he was years past his ability to credibly – or enthusiastically – write about the latest pop music personality or rock band, feeling mostly underwhelmed by the former, and far too familiar with nearly everything the latter were scavenging from the musical past to create their portmanteau styles. Well into middle age, he found himself – with a mixture of gratitude and alarm – developing a deep interest in the classical repertoire that people like Peter Alward had spent their careers fixing on to LPs and CDs.

His book is subtitled How I Fell in Love with Classical Music (and Decided to Rewrite its Entire History). Like the title, the book is ambitious, sprawling and prolix – longer in passages than it needs to be, repetitive in spots, and definitely not for a general audience. Much as classical music appears to the general public – and very much how Morley himself once viewed the music.

Morley’s growing obsession with classical music – including its more abstract and strident frontiers of modern concert or art music – came about, he admits, because of his vision that there is a single piece of music that he will be listening to at the moment of his death, an idea that preoccupies him given his irreversible proximity to retirement age. Which is bad news for anyone hoping that someone like Morley would perform the longed-for task of making classical music attractive to anyone under 50.

“Classical music when you are young,” Morley writes, “can seem all about death, being mostly written by the long-dead, and filled with quiet, comfortless dread, and not something you wish to engage with…but as you get older, and find your way around this elaborate other land, you appreciate it is more about the astonishing privilege of being alive, on the astonishing verge of not being.”

Growing up in the British industrial northwest, Morley became a music fan early on, collecting records based on what he’d hear on influential radio programs like BBC DJ John Peel’s, developing the sort of precocious and not-so-vaguely snobbish taste for the eclectic and the rare that usually marks music journalists. His curiosity inevitably pushed him toward classical music, and inspired the purchase of a budget label recording of Gustav Holst’s orchestral suite The Planets.

It was not an auspicious start. A science fiction fan, he picked the record based mostly on the cover art, but the music on the record sounded trite and familiar, thanks to the way that film composers – prime among them John Williams, who would strip mine Holst for his Star Wars scores – had plundered The Planets over the half century between when it was first performed and when the young Morley split the shrink wrap. “Because of what it influenced,” Morley writes, “it felt as though The Planets was the rip-off, because on a budget record it sounded thinner and tamer than the music that borrowed and stole from it, which was engineered to ceremonially fill cinemas and make you feel it as much as hear it.”

It took Morley decades to accumulate the context necessary to understand the historical importance of classical music, and to overcome his own aversion, based on assumptions about it being dull but worthy, and a status trinket for the middle and upper classes whose patronage has a reverse Midas Touch for culture commentators like Morley, living like so many journalists in the sunless shadow of Marxist academia.

I feel sorry for Morley when I read these long stretches of mea culpa. Because I was fortunate enough not to start life with the same assumptions about classical music being fusty, dated, elitist, and unrewarding for anyone truly living in the modern world. Thanks to a piano in the living room, weekly lessons from Miss Stokes around the corner, and my brother-in-law’s hi-fi in the basement, I learned to listen to and love classical music before later passions for prog rock, heavy metal, soul, punk. and jazz took hold.

Growing up in a working-class neighbourhood in the ‘70s, I could appreciate how much more rebellious it was to listen to Beethoven or Bach than whatever was on AM Top 40 or convulsing my schoolmates each school year. Years later – as a young music writer and photographer, living in little nightclubs where future stadium acts like White Zombie and Soundgarden would play on cramped stages barely a few inches above the beer-sticky floor and a few feet from my face – I had a day job selling CDs in the classical music department of one of the big Yonge Street music stores.

Perhaps it was England’s calcified class structure that held Morley back, but when he could finally admit his love for classical music, he took to essaying its virtues with missionary zeal; much of the book contains reworked articles he wrote and speeches he gave trying to explain the relevance of the music, and his optimism for its future in the timeless, placeless world of online streaming services. And like every music writer – Lebrecht’s book has them too – he compiles lists and playlists for the reader, to guide them through his scattershot thesis.

“I used to think classical music was old-fashioned and out of date,” Morley writes, “but I now realize it was just too modern. By modern, I mean it was concerned with all the workings of the mind, and how that reflected and created reality around it. By modern I mean a kind of energy that both grounds us in the here and now and sends signals of intent out into the future. Rhythmically, too, it was often way ahead of rock and pop, pressing all kinds of agitation and animation into its rhythms that make rock rhythms – if not the electronics of pop and hip-hop – seem increasingly tepid and obvious.”

Morley also tries to find an answer to the problem that’s beset the classical music business for decades – how to make it attractive to young people. He sees hope in the technological revolution that killed the major record label classical industry eulogized in Lebrecht’s book. The frantic activity of a century of recording – now uneconomical to continue – created a permanent catalogue of hundreds of years of music, from plain chant to baroque to Romanticism to serial music to minimalism, all of it available literally at the touch of a finger. To Morley’s mind, we’re living in the Eternal Now, where the idea that everything had its place in a daisy chain moving forward under the pitiless whip of progress toward some chimera of future perfection has finally revealed itself as absurd.

Where musical audiences once broke down on generational lines, parents and children can now enjoy the same music together, sitting together in arenas for reunion tours and bringing souvenir t-shirts home. The class stigma that once afflicted opera, ballet, and symphonies has evaporated as wealthy patrons have abandoned the concert halls for fundraising benefits for political, environmental, and social justice causes. The barriers – real or imagined – that kept the young Paul Morley away from classical music are gone, and he sees it as not just an opportunity but an imperative – a chance to make long-dead composers, once the misfits, radicals and bohemian tearaways of their time, relevant again, and perhaps even eke out a living for their still-breathing artistic descendents.

In other words, now that Paul Morley is thinking about himself on the verge of being history, he wants us to appreciate all that history he has come to survey from his place on the treeless plain of late middle age that’s given him perspective youth denied him. He sees now that all of those panicked record label executives, artistic directors and conductors weren’t merely trying to save their own jobs, but felt a responsibility “with the end of things and maintaining collective cultural memory.”

There’s something strangely familiar about Morley’s zeal to inspire what’s left of the classical music business to “act like it knows it is on a crusade to oppose soft thinking, banal interaction and weak minds.”

“If I made the rules,” Morley writes, “I would demand a world where the orchestra doesn’t chase audiences or try to make friends with them, hunting down a specifically targeted audience…In the end, the greater point is not reaching a wider audience, because to do so means sacrificing every single thing you do that means anything…”

He pleads against “marketing the music played by orchestras not as some sort of spa therapy, or teaching aid, or social welfare, but as something that contributes to our knowledge of music and therefore of what it is to be human, here in space, at this weird moment in time.”

If you substitute “liturgy” for “music played by orchestras” and “knowledge of music” with “worship of God” he might as well be arguing for the Latin Mass from the position of a trad Catholic. It’s an argument you’ll also hear from people pleading for the teaching of fundamental skills in art, or the preservation of the Western canon in literature.

And while I know that Paul Morley would probably be mortified to be accused of articulating what is essentially a conservative polemic against the flabby excesses and therapeutic impulses of the contemporary, it’s difficult not to recognize a pattern. And even if time buries Bach, Brahms, Berlioz, and Berio beneath the spoil of cultural amnesia, it’s the burden of Morley – of anyone who still cares about a future they’ll never see – to defend the artifacts of the past they needed to make their own life bearable, just enough that they’ll survive another generation in some recognizable shape.