Now that COVID-19 vaccinations are being made available across the country, Canadians find themselves facing important personal decisions about whether or not they should receive them—decisions which will require reflection, research, and prudence about a medical procedure which bears on personal physical health, social responsibility, and the inviolable dictates of conscience.

Now that COVID-19 vaccinations are being made available across the country, Canadians find themselves facing important personal decisions about whether or not they should receive them—decisions which will require reflection, research, and prudence about a medical procedure which bears on personal physical health, social responsibility, and the inviolable dictates of conscience.

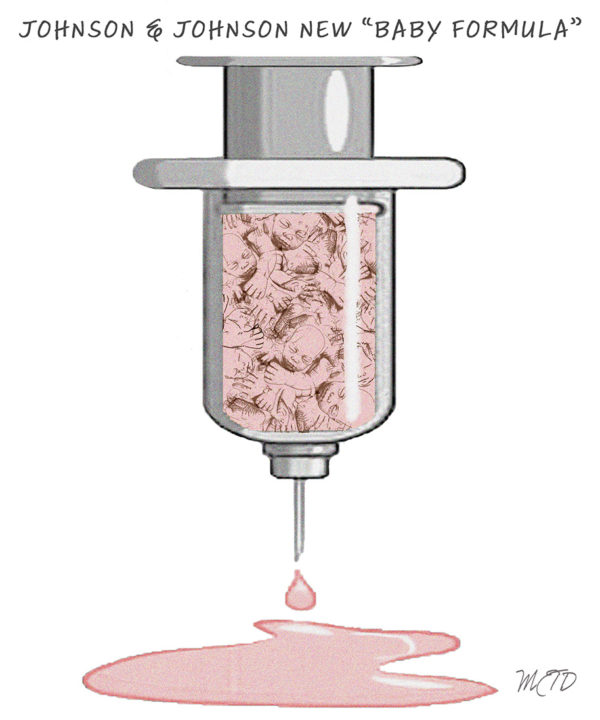

From reading the headlines in the press, however, one wouldn’t think that any such decision was at hand. On the subject of vaccines, our betters have spoken: there can be no higher moral good than thwarting the deadly scourge of COVID, and ethical concerns about the vaccine’s connection with the ongoing moral outrage of abortion is not only frivolous but a danger to public health. Statements of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, for example, which have indicated preferences for some vaccines over others on ethical grounds, have been roundly censured by pundits and public officials. Even to air any misgivings is an outrage, and anyone doing so is curtly reminded there is no greater moral priority than curbing the spread of the coronavirus pandemic.

Nothing, of course, could be further from the truth. As civic unrest in the wake of the death of George Floyd spread across the continent last year, all of the protocols and protections against COVID’s spread were held in abeyance. Public officials who had discouraged any kind of unsocially distanced activity were compelled not only to participate in these protests, but to bend a proverbial (and often actual) knee, genuflecting before a cultural juggernaut of moral outrage.

And yet, when COVID policy brushes up against the unspeakable atrocity of prenatal infanticide, all of the relaxed rules are reasserted. We are urged to pay no heed to the moral qualms that abortion-related therapies might occasion; indeed, we are hectored even for acknowledging that intelligent people of good will and sound judgement might have scruples and reservations. Instead, the clear instructions we have received amount to “shut up and do what you’re told.” As the Catholic Register’s editorial put it with such exquisite sensitivity and tact: “Here’s the bottom line: Get vaccinated.”

Such high-handed, cavalier commands would seem hard to square with the Catholic principle of subsidiarity, by which decisions are always to be delegated to the lowest level of competent authority—but leave such questions of principle aside. The confidence and tone of these injunctions about morally questionable injections is borne not on any principle but on the prevailing winds of the zeitgeist.

A counter-factual example makes this point especially clear. Imagine there is a range of COVID vaccines available, but all of them have some substantial connection to the evil — say, the oppressive institution of American slavery. Some vaccines contain the tissue of black slaves; others were only tested on them. Would the same political, cultural, and clerical authorities advise us, after some boilerplate about personal conscience, just to “get vaccinated”? Would their moral calculations still so easily arrive at the current conclusion: that ethical questions about vaccine production are so obviously outweighed by the common good? Indeed, to pivot from the counter-factual to the concrete, would the chorus of voices attempting to silence any dissent on these questions be quite so loud if it were known that the dead babies whose cells have been incorporated into some vaccines are those of marginalized racial minorities?

Rather than even acknowledging that vaccines connected to abortion present individual moral agents with important decisions to make, loud and increasingly impatient voices in the media, in politics, in culture, and in our churches are nudging us to fall in line. The vivid contrast between last summer and this spring is revealing. Their message to us is clear: we are to defer all the moral energy to the causes of which the elites approve and make distressing concessions and compromises whenever they don’t.

We must, therefore, insist on two crucial points. First, that abortion is a unique, iniquitous moral obscenity, and any procedures connected with it are profoundly morally problematic, no matter what mitigating circumstances exist. Secondly—and, in the present context, more importantly—there is an alarming danger in the current cultural message that moral qualms don’t matter, that the voice of conscience should simply be ignored.

In the 19th century, John Henry Newman wrote eloquently about this inner voice. He called conscience the “great internal teacher” which is “nearer to us than any other means of knowledge”: “a prophet in its information” and “a priest in its blessings and anathemas.” It was, for Newman, a kind of “Vicar of Christ,” speaking with conviction and clarity within (and to) the very heart of man. And more recently, and more darkly, we remind ourselves what a society can become when the voice of conscience has been muted. In the 1960s, Hannah Arendt noted that “evil in the Third Reich had lost the quality by which most people recognize it—the quality of temptation.”

There is nothing more dangerous than being told that the voice of conscience can be easily overruled and disregarded. Clearly, we all have, along with the solemn responsibility to follow our consciences, the equally important duty to inform them properly. But once that has been done, once our moral compasses have been set, we must follow their direction even when they set us against the headwinds of the world.

Thus, even in the midst of our life and death struggle with the global coronavirus pandemic, we must remind ourselves that something more precious than our own lives and those of the most vulnerable hangs in the balance: our very identity as moral agents, our integrity as people blessed with liberty, making use of the sacred gift of our freedom in the sight of Almighty God.