By Paul Tuns – Review

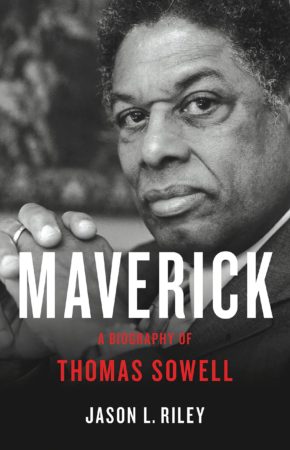

Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell

Jason L. Riley (Basic Books, $38, 290 pages)

I mentioned in my From the Editor’s Desk column that I greatly admired columnist George F. Will (still do). Another columnist I greatly admire and learn from is Thomas Sowell. I have more than 30 of his books on my shelves and have watched dozens of videos on YouTube. He is probably the best-known black conservative. Since reading last year that journalist and documentarian Jason L. Riley was writing a biography of Sowell, I have eagerly anticipated it and Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell does not disappoint.

I mentioned in my From the Editor’s Desk column that I greatly admired columnist George F. Will (still do). Another columnist I greatly admire and learn from is Thomas Sowell. I have more than 30 of his books on my shelves and have watched dozens of videos on YouTube. He is probably the best-known black conservative. Since reading last year that journalist and documentarian Jason L. Riley was writing a biography of Sowell, I have eagerly anticipated it and Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell does not disappoint.

This is not a conventional biography (I highly recommend Sowell’s autobiography A Personal Odyssey if you are interested in the details of his life), but rather “a treatment of Sowell’s ideas.” Riley does a terrific job connecting Sowell’s life experiences to his worldview, most notably his time as a student at the University of Chicago where he was influenced by Milton Friedman and George Stigler, but for the most part Riley focuses on Sowell’s writing. Writing about Sowell’s research on IQ and race, Riley says “he wasn’t fearful of what he might find” – and that attitude is true for whatever issue Sowell was researching. If there is a theme to Sowell’s life it is a strong commitment to facts, which influences his both his opinion-writing and books.

Sowell is an economist who spent a brief time in the classroom teaching before leaving the not-so-hallowed halls of the university for the Hoover Institution and full-time writing. His classroom was now the mass-media audience, whom he educated through his syndicated columns and television and radio interviews. Much of Sowell’s scholarship and writing has been on race, Race and Economics prominent among them, about which Riley reports: “The book also had a significant impact on a young attorney in the Midwest named Clarence Thomas, who independently had reached similar conclusions about racial inequality but was unaware of other blacks who shared his viewpoint.” Many of Sowell’s books, Riley writes, “delved … deeply into the social and cultural significance of cultural patterns.” Sowell applied economic principles to race and found that discrimination played a relatively small role for the different educational and employment outcomes of blacks compared to whites, and finds that affirmative action does little for blacks at the bottom rungs of the economic and educational ladders.

Sowell has not necessarily been successful in convincing the American public. In his 1990 book Preferential Policies he addressed the issue of reparations to blacks, a topic once again being debated south of the border. He wrote at the time, “The wrongs of history have been invoked by many groups in many countries as a moral claim for contemporary compensation.” Sowell continued: “The biological continuity of the generations lends plausibility to the notion of group compensation – but only if guilt can be inherited.” If guilt was not inherited and compensation was paid, Sowell did not view the redistribution of wealth as justice but “simply windfall gains and windfall losses among contemporaries.” Sowell’s great gift as a pundit was his plain-spokenness.

It might be hard to imagine what it was like being one of the only black conservatives in the 1970s and 1980s. William F. Buckley, editor of National Review, joked that Sowell and his friend, Walter Williams, another black economist with a syndicated column, were not allowed to fly in the same plane lest it crash and the movement lose both black conservatives. He was certainly a beloved figure within the conservative movement, but Sowell’s intellectual honesty did not endear him to so-called black leaders (an idea that repulsed Sowell – no one speaks of white leaders), and you would think that being labeled a traitor to his race would have stung. But Sowell has written: “Self-respect is the most important thing. Without it, the world’s adulation rings hollow. And with it, even venomous attacks are like water off a duck’s back.” This is the necessary disposition because he “marched to his own drummer.”

Reading Riley’s excellent intellectual biography will delight conservatives who grew up with Sowell’s writings and introduce those new to him to a vast world of ground-breaking, fearless writing.